Trees and shrubs

Where is aspen, there is cambium.

Comment: Cambium, the inner bark of trees is nutritious and perfect as emergency food. (T.S.)

Kus haab, sääl mähi.

Seletus: Mähi on puu koorealune kasvav kiht, mis on söödav ja toitev. (T.S.)

Back in the old days, there lived an unspeakably rich and evil manor lord. He forced the people of his parish to do heavy labour both night and day, and would ceaselessly find fault with the workers for quite insignificant things. In addition to his great wealth, he had two sons and a daughter. When the girl had come of age, suitors came calling on her, but her stingy father said he wouldn’t give his daughter to anyone other than the type of man he himself was: rich and stingy and a big penny-pincher. What a sorry state of affairs!

At long last, a strange, unknown gentleman came courting her; he was warmly received. You could tell from the suitor’s clothing that he was a rich man, and when he placed a gold, jewelled ring on his betrothed’s finger as he bid her farewell, everyone’s joy knew no bounds, neither, however, did anyone start inquiring as to where the suitor was from. Then began preparations for a grand wedding, the day of which also arrived before long. The wedding had arrived, the guests were merry and gathered around the drinking tables, but they were still missing one thing: the groom hadn’t come. At long last, the groom also showed up, wearing dazzling clothes, seated in a six-horse carriage, and the wedding guests welcomed him gaily. The bride was merry and the wedding went on and on. At last, all the wedding guests were exhausted and drifted off to sleep from their fatigue.

When everyone was already sleeping, the groom said to his bride: “My dear wife, we will leave now, because we may not stay here another day; I have many great things to attend to at home and must be there before sunrise.” The bride did protest at first, but when the carriage rolled up to the doors at dawn, they both dressed and left without telling the others. The wedding guests were certainly sad when they awoke that morning, but there was nothing they could do. When the carriage reached the shore of the sea at sunrise, they rowed across it to the opposite shore. There, the young couple entered a majestic house that glittered with gold and pearls. The house held more beauty than it needed. The young bride had never seen such a sight with her own eyes before. She went to rest, but when she woke up, she could no longer find her husband at home. Two girls came to dress her: she asked them about her husband, too, but they weren’t able to utter an O or an A about it. When the young bride couldn’t get any clear details about her husband, who vanished from home every morning and returned only late each night, she secretly started keeping an eye on him.

One morning, she observed her husband get out of bed, turn himself into a snake, and disappear beneath the bed. The young bride froze as stiff as a tree in shock when she saw this. She thought about the frightful sight that whole day, and when her husband returned home that night, she asked him about it. The man didn’t want to say anything, but when the woman just wouldn’t give up, he finally explained: “I am the king of the sea serpents and must look over my kingdom every day and go to rule my subjects!” The woman wore a satisfied look, but great dread and fear filled her heart. They carried on living like that for many, many more good years. They already had three children, too.

One day, the woman came to her husband and requested that he allow her to go visit her parents. This wasn’t at all to the man’s liking, but he handed the woman a spindle of tow and said: “When you have spun this tow, then you may go on your merry way and see your parents!” This promise raised the woman’s spirits and she started spinning briskly, but soon saw that her joy had been premature, since although she spun the tow for nights and days on end, the spindle didn’t shrink in the least. She started weeping in misery. While she wept, a little grey man entered the room, comforted her, and said very kindly: “When you start spinning again, then shake the spindle hard!” The woman followed the old man’s advice and instruction, and lo and behold: tiny worms tumbled out like rain, the spindle started to shrink, and it finally ran out.

Now, the woman was overjoyed, because she could go to her long-missed homeland to see her parents and relatives. The boat had already been pushed into the sea for the journey. She held her three children close and with her husband’s help, they soon reached the opposite shore of the sea. The woman stepped on land with her children, but the man remained sitting in the boat and said: “I will wait here until you return. When you arrive, call me by saying:

Bring the boat, bring it about,

to gentle mother, to the kids!

If you call out those words and do not see me, then call out:

Little wave, row, reach,

show me sea foam bloody!

And if the sea then starts to foam, you will know that I have met my death in the deep currents!” The woman then left with her children. When she reached her father’s house, they were received with great joy. She didn’t speak a word about her life or her husband, though her relatives and friends pried incessantly. But then, they asked the children. The children told their uncle their father’s story. The uncle and other relatives plotted to divorce her from him, and decided to kill the man. What was said was done. Unbeknownst to the woman, they went to the edge of the sea and summoned the man:

“Bring the boat, bring it about,

to gentle mother, to the kids!”

The man came, and they seized and killed him. When the woman went to the sea and summoned her husband with the familiar words the next morning, despite her parents and relatives forbidding her from doing so, he did not appear. Then, the woman said:

“Little wave, row, reach,

show me sea foam bloody!”

When she spoke these words, the sea started foaming dreadfully. Now, the woman knew her husband had died. She began lamenting her husband dreadfully.

The grey man came to her and asked: “Hear, woman – what is your trouble? Can I perhaps help you again?” “Dear old man, my wish would be to become a tree: a good tree who is of use to the coming generation and who benefits others – and my children must be together with me!” The grey old man took his cane, tapped it three times against the woman’s head, and did the same to the children, who had come with their mother. And can you imagine what happened then! Suddenly, a beautiful, straight birch was standing before him. The woman grew into a birch tree, and her children grew into the bark around her. That is why the birch has three-layered bark to this day: first the inner bark, then the top white bark, and thirdly the one that flutters in the breeze and must endure hardship. That is the very youngest child – all because he was careless and revealed his parents’ secrets. That is how the birch tree came into this world.

Vanal ajal elanud üks väga ütlemata rikas ja kuri mõisahärra. Ta sundis oma valla rahvast öösel ja päeval raskele tööle ning nurises ühtelugu üsna tühja asja pärast tööliste üle. Peale suure rikkuse oli tal ka kaks poega ja üks tütar. Kui tütar juba täisealiseks oli saanud, tulid talle kosilased, aga ihnus isa ütles, et ei anna oma tütart kellelegi muule kui üksnes niisugusele, nagu ta ise on: rikas ja ihnus ning kange kokkuhoidja. Hea lugu küll!

Viimaks ometi tuli üks võõras tundmata härra kosja; teda võeti rõõmuga vastu. Riietest oli aru saada, et kosilane rikas mees on, ja kui ta jumalaga jättes pruudile kalliskividega kuldsõrmuse sõrme pistis, oli kõikide rõõm otsata ega küsitud pikemalt kosilase asupaiga järele. Siis algas kõva pulmade vastu valmistamine, mis peagi ka kätte jõudis. Pulm oli koos, rahvas oli rõõmus joomalaudade ümber, aga veel puudus neil midagi – peigmees ei olnud tulnud. Viimaks ilmus ka hiilgavates riietes peigmees kuue hobuse tõllaga ja pulmalised võtsid ta rõõmuga vastu. Pruut oli rõõmus ja pulm kestis ühtelugu edasi. Viimaks jäid kõik pulmalised rammetumaks ja uinusid väsimuse ja une kätte magama.

Kui kõik juba uinusid, ütles peigmees mõrsjale: „Armas abikaasa, teeme nüüd minekut, sest teiseks päevaks ei või me siia jääda; mul on kodus väga suuri talitusi, et enne päevatõusu kodus pean olema.” Mõrsja pani küll esiotsa vastu, aga kui koiduvalgel tõld ukse ette vuras, panid mõlemad end riidesse ja sõitsid ilma teiste teadmata minema. Pulmalised olid hommikul küll kurvad, kui üles ärkasid, aga ei võinud sinna midagi parata. Kui tõld päevatõusu ajal mere kaldale jõudis, siis sõudsid nad sealt laevaga üle mere teise poole kaldale. Seal astus noorpaar uhkesse majasse, mis kulla ja pärlite käes säras. Ilu oli majas rohkem kui tarvis. Noor mõrsja ei olnud veel oma elu sees niisugust oma silmaga näinud. Väsimusest heitis ta puhkama, aga kui ta üles ärkas, ei leidnud ta enam meest kodust. Kaks tüdrukut tulid teda riidesse panema; ta küsis ka nende käest oma mehe järele, aga need ei teadnud ka u-d ega a-d vastata. Kui noor mõrsja oma mehe üle selgust ei saanud, kes iga hommiku kodust ära kadus ja alles õhtu hilja koju tuli, hakkas ta salaja tema järele valvama.

Ühel hommikul nägi ta, kuidas mees voodist välja tuli, muutis ennast maoks ja kadus ära voodi alla. Noor mõrsja ehmatas seda nähes puukangeks. Ta mõtles kogu päeva selle hirmsa loo üle järele ja kui mees õhtu koju tuli, päris seda asjalugu järele. Mees ei tahtnud midagi sellest rääkida, aga kui naine sugugi järele ei andnud, seletas ta viimaks: „Ma olen meremadude kuningas ja pean oma riiki iga päev vaatamas ja oma alamate üle valitsemas käima!” Naine jäi küll rahule, aga tema südames oli suur mure ja kartus. Niiviisi elasid nad mitu ja mitu head aastat edasi. Neil oli ka juba kolm last.

Ükskord astus naine selle palvega mehe ette, et lubaks teda oma vanemaid vaatama minna. Mehele ei olnud see palve sugugi meele järele, aga ta andis ühe koonla naise kätte ja ütles: „Kui selle koonla oled ära kedranud, siis võid rõõmuga oma vanemaid vaatama minna!” Naine rõõmustas mehe lubaduse üle ja hakkas kibedasti ketrama, aga varsti nägi, et tema rõõm oli olnud enneaegu, sest kuigi ta küll ööd kui päevad ketras, ei vähenenud koonal sugugi. Ta hakkas haledasti nutma. Kui ta nuttis, astus üks hall mehike tuppa, trööstis teda ja ütles väga lahkelt: „Kui sa jälle ketrama hakkad, siis raputa koonalt kõvasti!” Naine tegi vanakese õpetuse ja nõu järele ning vaata imet, peenikesi usse sadas kui vihma maha ja koonal hakkas vähenema ja lõppes viimaks otsa.

Nüüd oli naine rõõmus, sest nüüd võis ta kaua igatsetud isamaale minna oma vanemate ja sugulaste juurde. Paat oli teele minemiseks juba merre lastud. Ta võttis oma kolm last ligi ja mehe abiga jõudsid nad peagi teisele poole mere kaldale. Naine astus oma lastega maale, aga mees jäi paati istuma ja ütles: „Ma ootan teid siin tagasitulekuni. Kui siia jõuate, siis hüüdke mind:

"Too paati, tuleta paati,

hella ema, laste vastu!"

Kui te aga nõnda olete hüüdnud ja mind ei näe, siis hüüdke:

"Lainekene, sõua, jõua,

näita mul vahtugi verine!

Ja kui siis meri vahutama hakkab, siis teadke, et ma vetevoogudes surma olen leidnud!”

Naine läks nüüd lastega minema. Kui ta oma isakoju jõudis, võeti neid suure rõõmuga vastu. Oma elust ja mehest ei rääkinud ta ühtainust sõnagi, kuigi küll sugulased ja sõbrad järelejätmata pärisid. Siis küsisid nad aga laste käest. Lapsed rääkisid oma onule, kuidas nende isaga lugu on. Onu ja teised sugulased pidasid nõu naist tast lahutada ja võtsid nõuks ta ära tappa. Mis mõeldud, sai tehtud. Nad läksid ilma naise teadmata mere äärde ja kutsusid meest:

„Too paati, tuleta paati,

hella ema, laste vastu!”

Mees tuligi, nad võtsid ta kinni ja tapsid ära. Kui naine teisel hommikul vanemate ja sugulaste keelust hoolimata mere äärde läks ja tuttava sõn aga oma meest kutsus, ei ilmunud teda mitte. Siis lausus naine:

„Lainekene, sõua, jõua,

näita mul vahtugi verine!”

Kui ta oli nii ütelnud, hakkas meri hirmsasti vahutama. Nüüd teadis naine, et tema mees surma oli saanud. Ta hakkas oma mehe järgi hirmsasti ahastama.

Üks hall mehike tuli tema juurde ja küsis: „Kuule naine, mis sul viga on? Kas ehk mina võiksin sind jälle aidata?” – „Armas vanake, minu soov oleks puuks saada, üheks heaks puuks, kellest tuleva põlve rahvale kasu kasvab ja tulu tõuseb – ja minu lapsed peavad minuga ühes olema!” Vana hall mees võttis oma kepi, lõi sellega kolm korda naisele pähe, niisamuti ka lastele, kes emaga ühes olid tulnud. Ja vaata imet, mis siis sündis! Korraga seisis tema ees ilus sirge kask. Naine kasvas kasepuuks ja lapsed kasvasid kooreks tema ümber. Sellepärast on kasel veel tänapäevani kolmekordne koor: esiteks alumine koor, teiseks pealmine valge koor ja kolmandaks see, mis tuule käes lipendab ja vaeva nägema peab. See on kõige noorem laps – sellepärast, et ta kergemeelne oli ja oma vanemate saladused avaldas. Nõnda oli kasepuu ilma sündinud.

Once upon a time there was a man and a woman. They had three daughters: the youngest; the eldest, and the middle one, of course. The berry forest was close to their home and they decided to pick berries there.

The youngest daughter was diligent and would do any work. As they arrived in the berry forest, they saw there were shrivelled strawberries growing on the clearing floor. The eldest and the middle daughter did not want to pick these strawberries and they said: „Why pick these tiny things! We had better go and find the places with bigger berries.“

The youngest daughter said: „I am not going. I will pick these here. You go if you want to!“ and she stayed there alone to pick the little strawberries. The middle and the eldest daughter walked and walked around the forest but it was still early [early summer] and the bigger strawberries were still white. So, they did not get anything. The evening was arriving and they returned to the clearing where the youngest daughter was still picking. Her stomach was full and her basket was full. Having seen this, the eldest daughter became jealous and, considering it with the middle sister behind the tree, said: „Let’s kill her!“ So they did.

There was a lane running through the forest and they buried her near this lane. But how to remember her grave? They planted a birch tree thereon. The lane was for the merchants, who travelled from one town to another.

So, the sisters went home. They shared the younger sister’s strawberries between them. The mother and father asked: „Where is the youngest daughter?“ „We didn’t see her at all. We went to the forest together but she was picking on her own and we were on our own. We know nothing about her.“ They denied it all.

Mother’s and father’s hearts were aching, as it was already getting dark. They heard the merchants coming and did not want to make a fuss about their daughter missing from home.

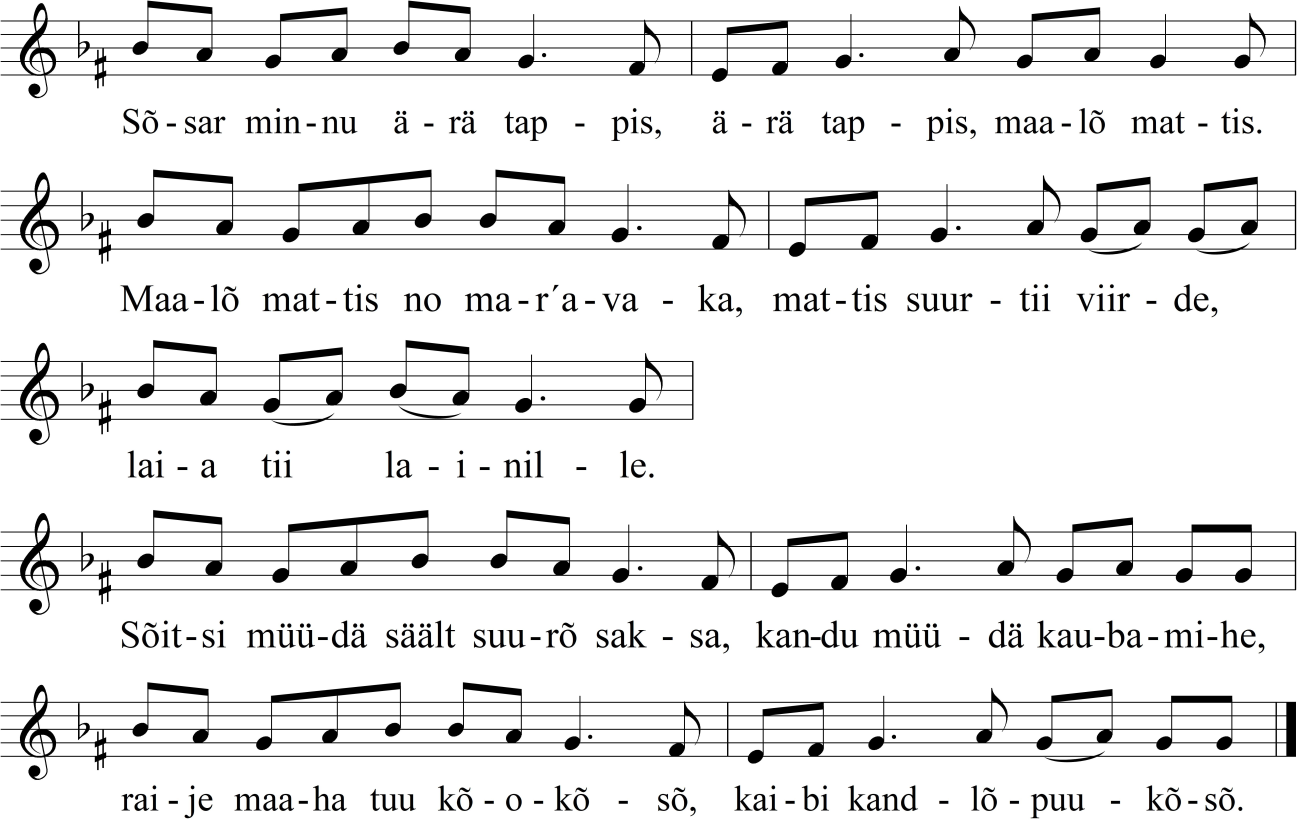

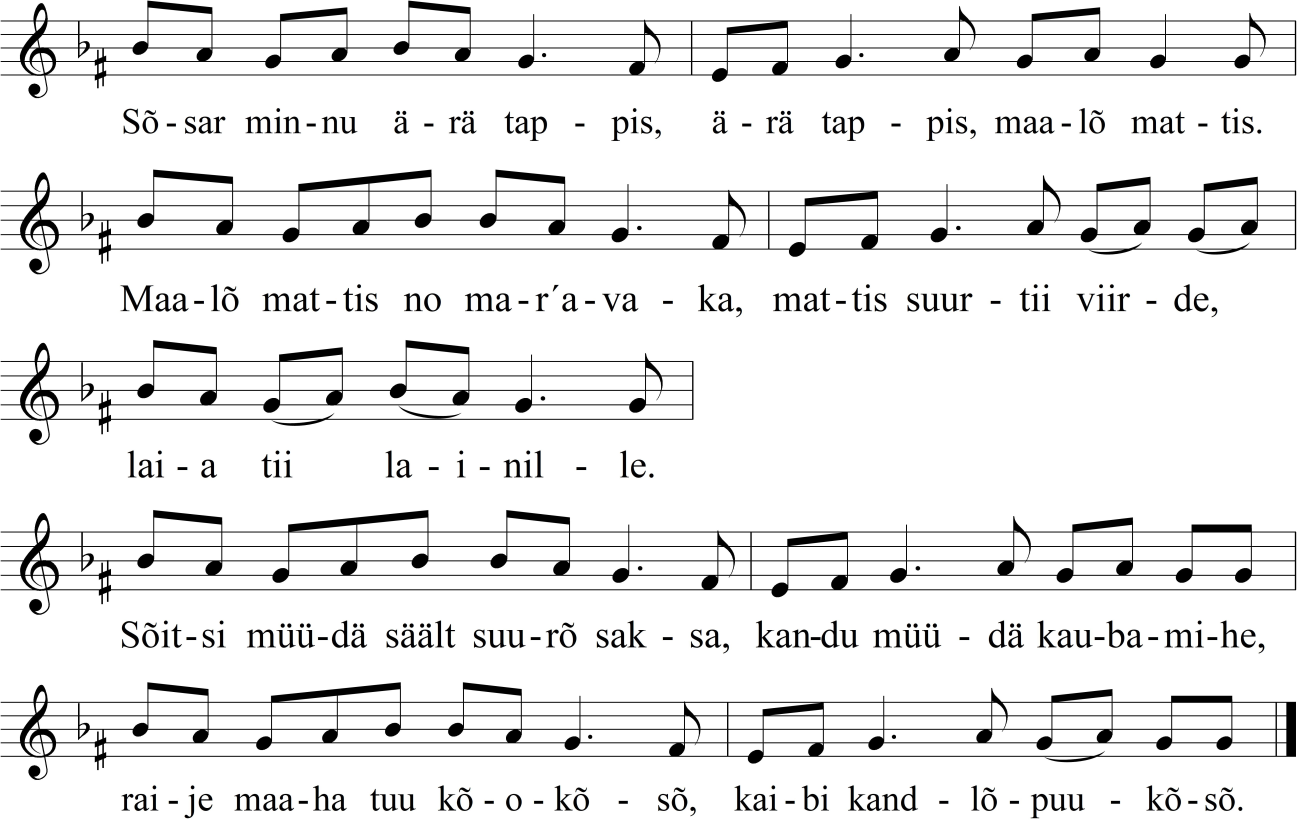

After a while, some merchants came to the village and rode along the same lane where the birch tree was planted nearby. One of the merchants was a young boy and he chopped down the birch tree and made a harp (kannel) from it. He made the harp’s box [it was made from one tree] and the harp started to play without any strings, and it played like this:

Sister killed me, sister buried me into the earth.

She buried my berry basket, next to the great lane, on the waves of the wide lane.

Great gentlemen passed through, merchants rode through.

They chopped down a birch tree, they dug up a harp tree.

The evening was arriving and merchants went to seek a lodging house in the village. The harp kept singing like that all the time. As there were many merchants, they split themselves between the farms. The merchant with the harp stayed with the family whose youngest daughter was missing. The mother and father heard this harp play and they asked: „Could we have this harp, too.“ The merchant gave it to them and the harp kept playing the same way. As it was given over to the sisters, the harp no longer played.

This is how it was found out that they had killed their sister.

Elasid eit ja taat. Neil oli kolm tütart: noorem, vanem ja muidugi ka keskmine. Marjamets asus nende kodu lähedal ja nad otsustasid sinna marjule minna.

Noorem tütar oli usin ja sai iga tööga toime. Kolmekesi marjule jõudes nägid nad, et raiesmikul kasvasid kidurad maasikad. Vanem ja keskmine tütar ei tahtnud neid maasikaid korjata ja ütlesid, et: „Oh, mis me ikka neid korjame, me läheme otsime parem, kus on priskemad marjad.”

Noorem tütar ütles: „Ei mina enam otsima lähe, mina korjan siin, minge teie pealegi!” ja jäi üksi raiesmikule pisikesi maasikaid korjama. Keskmine ja vanem tütar käisid ja käisid mööda metsa, aga oli varajane aeg ja maasikad olid veel valged. Nii nad ei saanudki mitte midagi.

Õhtu hakkas juba kätte jõudma ning nad läksid tagasi raiesmikule, kus noorem tütar ikka veel korjas. Temal oli kõht täis ja korv täis. Vanem tütar läks seda nähes kadedaks ja jäi keskmisega puu taha aru pidama ning ütles:

„Tapame ta ära!” Tapsidki noorema ära. Metsast viis läbi tee ja nad matsid ta tee veerde. Selleks, et meeles pidada, kus sõsara haud on, istutasid sinna peale kasepuu. Koju jõudes küsisid isa emaga:

„Kus noorem tütar on?”

„Aga meie ei näinudki teda. Metsa läksime küll ühes, aga tema korjas omaette ja meie omaette. Meie ei tea temast midagi.”

Salgasid kõik maha. Isal-emal jäigi süda valutama.

Mõne aja pärast tulid külla kaupmehed ja sõitsid seda sama teed mööda, kuhu veerde oli kasepuu istutatud. Üks kaupmees oli noorem poiss ja tema raius kase maha ning tegi endale kandlepuu. (Noh, vanasti olid targad mehed.) Kannel hakkas ilma keelteta mängima ja mängis nii:

Õhtu hakkas kätte jõudma ja kaupmehed läksid küla peale öömaja otsima. Kannel kogu aeg laulis niimoodi. Kuna kaupmehi oli palju, siis nad jagasid endid talude vahel ära. Kandlega kaupmees sai öömajale selle pererahva juurde, kust noorem tütar oli ära kadunud. Isa emaga kuulsid kandlemängu ning palusid:

„Andke mulle ka toda kannelt”.

Kaupmees andis ja kannel mängis niimoodi isa käes ja ema käes. Anti kannel sõsarate kätte, aga kannel nende käes ei mänginud. Ja nii saadigi teada, et nemad oma sõsara on ära tapnud.

If a birch has little leaves like mice ears, the fishing time is over.

Kui kaseleht on hiirekõrva suurune, siis on kalaaeg möödas.

John grows (lit. continues) willow bark to the tree and Peter presses the rest.

Comment: From St. John's Day and St. Peter's Day, the willow bark sticks to the wood/tree. According to the Seto local Orthodox calendar, they are on July 7 and 12 (according to the regular calendar, June 24 and 29). (T.S.)

Jaan jätkab (pajukoore puu külge), Peeter pigistab päragi.

Seletus: Jaani- ja peetripäevast alates jääb pajukoor kinni. Need on Setomaa kohaliku kalendri järgi 7. ja 12. juulil (tavalise kalendri järgi 24. ja 29. juunil). (T.S.)

Three brothers and their wives lived together, and the men’s sister lived there, too. The brothers started debating:

“Why do we have to feed this sister of ours while we’ve got to feed our wives as well?”

They decided to take their sister out into the forest and leave her there. So, they did, coaxing her out, sticking her in an oak beehive and wedging it shut with a rowan branch so their sister couldn’t come home. At home, they told their wives that their sister got lost, but she was sure to return home. But the youngest brother’s wife sensed something was wrong. She went to heat the sauna and sang:

Come warm the sauna, sister-in-law!

Steep the bath broom1, sister-in-law!

Then she heard someone sing back from the forest:

I cannot come, sister-in-law!

I’m within an oaken beehive, behind a rowan branch!

The brother’s wife realised her sister-in-law was no longer alive. She cried bitter tears, but dared not speak to her husband about it. Yet, the rowan branch started to grow. It grew and grew, and grew into a rowan tree with a great cluster of berries at the crown. In that forest lived a father and his son. They would go out into the woods to cut down trees. One day when they passed the rowan tree on their way home, the boy broke off a cluster of berries and took it with him. At home, he stuck it into a crack between two boards in the wall. The next morning, the father and son go out into the forest, in the evening, they come home – and their little chamber has been heated, cleaned, and food has even been put in the oven to cook! This happens the next day again, and for a third one, too. The men can’t work out who has been coming to do these things.

The boy goes to a wise man.

The wise man says: “It is that cluster of rowan berries you brought home. When you leave, it turns into a girl. You can keep her in the form of a girl by pretending to go out into the forest, but don’t go – you hide yourself. When she turns into a girl, then wrap your arms around her tight and do not let her go. She will scream and beg; she will transform into a bird and a spindle. But don’t let her go until she turns back into a girl again!”

So it went. The girl sure screamed and begged and cried, but the boy wouldn’t let her go. The girl turned into a bird and a spindle; she transformed several times until she tired out. Then, she turned back into a girl again and remained there, becoming the boy’s wife. They lived well and happily: the girl cooked, washed the father and son’s laundry, took care of them in every respect, and they went out working in the forest. But then, her husband started saying:

“Listen, we’ve been living here for a long time now. Let’s go and visit your brothers, too.”

The girl doesn’t want to go.

“Well, let’s go anyway!”

So, they finally went. As soon as they showed up in the yard, the brothers were scared out of their wits and asked their sister’s forgiveness. She gave it, too. And so, they stayed living in that forest.

1 A whisk, a bundle of fresh or dried tree shoots soaked in hot water, used for whipping oneself or others in the sauna to open pores.

Elas kolm venda naistega koos ja meeste õde elas ka. Vennad hakkasid arutama:

„Mis me seda õde peame söötma, isegi oma naised sööta.”

Otsustasid õe metsa viia. Viisidki, meelitasid sinna, panid tammepuust tehtud taru sisse ja sellele pihlapuust pulga ette, et õde koju ei saaks tulla. Kodus rääkisid naistele, et õde eksis ära, küll ta koju tuleb. Aga kõige noorem vennanaine taipas, et midagi on lahti. Ta läks sauna kütma ja laulis:

Tule sauna küttema, meheõde!

Veere vihta haudema, meheõde!

Siis ta kuulis, et metsas laulab keegi vastu:

Ei saa veereda, vennanaine!

Olen tammise taru sees, pihlapuise pulga taga!

Vennanaine sai aru, et meheõde ei ole enam elus. Ta nuttis väga, aga mehele rääkida ei julgenud. Aga pihlapuust pulgake hakkas kasvama, muudkui kasvas, ja kasvas sellest pihlakas ning sellel oli suur marjakobar. Seal metsas elas isa pojaga, nad käisid metsas puid raiumas. Ükskord, kui nad metsast koju pihlakast mööda läksid, murdis poiss marjakobara ära ja viis koju. Kodus pani seinapalkide vahele. Järgmisel hommikul lähevad isa ja poeg metsa, õhtul tulevad koju – toakene soojaks köetud, ära koristatud ja isegi söök ahju pandud! Teine päev jälle ja kolmas ka. Mehed ei oska arvata, kes siin käib niimoodi tegemas. Poeg läheb targa juurde.

Tark ütleb:„See on seesama pihlakobar, mille sa tõid. Kui te ära lähete, siis muutub see tüdrukuks. Sa saad teda niiviisi tüdrukuna hoida, et lähete justkui metsa, aga sina ära mine, peida ennast ära. Kui ta siis tüdrukuks muutub, võta tal ümber kõvasti kinni, ära lahti lase. Ta karjub ja palub, muutub linnuks ja kedervarreks. Aga ära enne lahti lase, kuni uuesti tüdrukuks muutub!”

Nii oligi. Küll tüdruk karjus ja palus ja nuttis, aga poiss ei lasknud lahti. Tüdruk muutus linnuks ja kedervarreks, mitu korda muutis ennast, kuni väsis. Siis muutus uuesti tüdrukuks tagasi ja jäigi sinna elama, läks pojale naiseks. Nad elasid hästi ja õnnelikult, tüdruk tegi süüa, pesi isa ja poja pesu, hoolitses nende eest kõiges ja nemad käisid metsas tööl. Aga mees siis hakkas rääkima:

„Kuule, me oleme juba kaua elanud siin. Läheme su vendi ka vaatama.”

Tüdruk ei taha minna. „No lähme ikka!” Läksidki siis lõpuks. Nii kui õue peale sõitsid, olid vennad kole hirmunud ja palusid õe käest andeks. Tema andis ka. Ja nii jäidki siis nad metsa elama.

You must not strike an animal with a rowan whip because it stops the growth.

Pihlakavitsaga ei tohi looma lüüa – paneb kasvu kinni.

One day, long ago, it was raining. An old man sat alone in his chamber. He took an axe and went to fetch wood from the forest. In the forest, he went to a tree and started chopping it down. Right away, a voice called out from the tree: “Hear, man! Do not strike me anymore! I will give you whatever you ask.” The man thought for a little while, and then asked: “I suppose you could make me so rich that when I go home, all my sheds and crates will be filled with grain.” The tree said: “Go home, you’ll find what you ask.” The man listened to the tree and went home. At home, all the sheds and crates truly were filled with grain; the man became boundlessly rich.

But soon, the man had a hankering to become the parish elder so he could run his own affairs. He went back to the tree and started chopping. Right away, the tree pleaded: “Hear, man, do not strike! I will give you everything you want!” The man said right back: “Make me the parish elder, then!” The tree promised it and the man went home. The people immediately made him parish elder.

He’d been parish elder for quite a while, and then, he hankered to become the manor lord. He went to the tree and started chopping. The tree cried: “Don’t chop! I’ll give you what you want!” The man said: “I’d like to become the lord of the manor!” The tree replied: “Go home, it will be so.” He goes home and he had become the lord of the manor. '

The man lived like that for a while, but then hankered to become a duke. He went straight to the tree and started chopping. The tree begged: “Dear man! Don’t chop anymore!” The man said right back: “Make me a duke, then! Then I won’t chop anymore.” The tree said: “Well, go home! You’ll become one.” The man went home. Before long, he was made a duke.

But soon, that life turned boring for him again. He wanted to become a king. The man went to the tree and told it his wish: that he longed to become king. The tree replied: “Oh, what misfortune. You’ve gone too far! You must become a tree like me and weep for your pride in the strong winds.” And instantly, the man turned into a tree. Today, they say that when a tree screams – when it cries out, rubbing against another tree – it’s “the old man weeping for his pride”.

Kord sadanud ühel päeval vihma. Üks vana mees istus üksi oma toas. Ta võttis kirve ja läks metsast puid tooma. Metsas läks ta puu juurde ja hakkas raiuma. Kohe hüüdis üks hääl puu seest: „Kuule mees! Ära löö enam mitte! Ma annan sulle, mis sa aga küsid.” Mees mõtles natukene aega ja siis küsis: „Eks tee mind nii rikkaks, et kui ma koju lähen, siis on kõik aidad ja kastid vilja täis.” Puu ütles: „Mine koju, küll sa leiad.” Mees kuulas sõna ja läks koju. Kodus olnudki aidad ja kastid vilja täis, mees saanud otsata rikkaks.

Mehel tõusis aga varsti himu vallavanemaks saada, et siis on oma asjad käes toimetada. Ta läks jälle puu juurde ja hakkas raiuma. Puu kohe küsima: „Kuule mees, ära löö! Ma annan sulle kõik, mis tahad! Mees kohe: „Eks tee mind vallavanemaks!” Puu lubas seda ja mees läks koju. Kohe valinud inimesed ta vallavanemaks.

Oli juba tükk aega vallavanem, seal tuli tal himu mõisnikuks saada. Ta läks puu juurde ja hakkas raiuma. Puu vastas: „Ära raiu! Ma annan sulle, mis tahad!” Mees küsis: „Ma tahan mõisnikuks saada!” Puu vastas: „Mine koju, küll saad mõisnikuks.” Läheb koju ja saanudki mõisnikuks.

Elas tükk aega, seal tulnud tal nüüd himu vürstiks saada. Kohe läks ta puu juurde ja hakkas raiuma. Puu paluma: „Kulla mees! Ära raiu enam mitte!” Mees vastu: „Eks tee mind vürstiks! Siis ma enam ei raiu.” Puu ütles: „Mine aga koju! Küll siis vürstiks saad!” Mees läks koju. Peagi tõstetud ta vürstiks.

See elu läinud temale aga varsti jälle igavaks. Ta tahtis kuningaks saada. Mees läks puu juurde, rääkis oma soovi ära, et igatseb kuningaks saada. Puu vastas: „Oi õnnetust. Sa lähed liiale! Sa pead samuti puuks saama ja kange tuule ajal oma uhkuse pärast nutma.” Kohe saanudki mees puuks. Tänapäeval öeldakse, kui puu karjub – siis, kui teine teisi vastu hõõrudes piriseb –, et „vana mees nutab oma uhkust”.

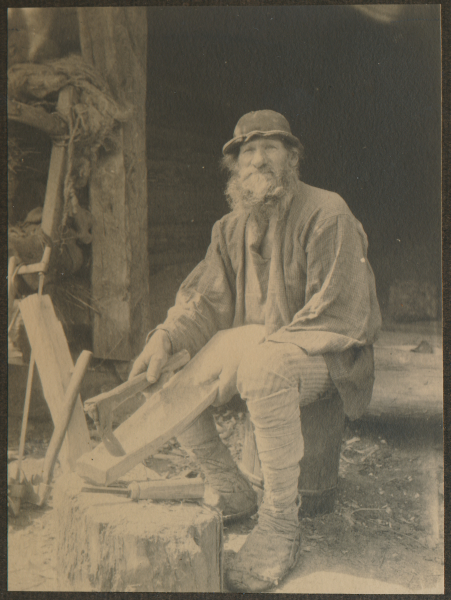

Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald. Eesti rahva ennemuistsed jutud 1866. Helde puuraiuja. Estonian fairy tales 1866. The kind woodcutter.

Once in times long past a woodcutter went to the forest to chop some wood. He came up to a birch and waved his axe, and the birch said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! I am young and have many children. What will they do without me?"

The woodcutter took pity on the birch. He came up to an oak and was about to chop it down but the oak saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter. I'm not yet fully grown and my acorns aren't ripe yet. If they are destroyed now no grove will ever spring up around me." The woodcutter took pity on the oak. He came up to an ash and wanted to chop it down but the ash saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! Only yesterday did my bride and I plight our troth. What will become of her if I am chopped down?"

The woodcutter took pity on the ash. He came up to a maple and was about to chop it down but the maple said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! For my children are small and have been taught no trade. They will perish without me."

The woodcutter took pity on the maple. He came up to an alder and wanted to cut it down but the alder saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! This is just the time when I feed the tiny wood bugs with my milk. What will become of them if I am chopped down?" The woodcutter took pity on the alder. He came up to an aspen and wanted to chop it down but the aspen said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! What was life given me for but for me to rustle my leaves in the wind and frighten the highwaymen at night! What is to become of good and honest folk if I am chopped down?"

The woodcutter took pity on the aspen. He came up to a bird- cherry and wanted to chop it down but the bird-cherry saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading ttones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! I am in full bloom now and the nightingales like to perch on my branches and sing their songs. If I am chopped down they will fly away and their songs will be heard no more."

The woodcutter took pity on the bird-cherry. He came up to a rowan and wanted to chop it down but the rowan said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! I have just come to full bloom and will soon be covered with clusters of berries. On these berries the birds will feed in autumn and winter. What will become of them if I am chopped down?"

The woodcutter took pity on the rowan. "It's no use, I'll never be able to bring myself to cut down any of the leaf-bearing trees!" said he to himself.

"I'd better try my luck with the fir trees."

He came up to a spruce and wanted to cut it down but the spruce saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter! Wait till I grow to my full height, for then you will be able to make floorboards of me. Now, while I'm still growing, people can take joy in the sight of my green branches all the year round."

The woodcutter took pity on the spruce. He came up to a pine and was about to chop it down but the pine saw the axe in his hand and said in pleading tones:

"Do not kill me, woodcutter!" it begged. "I am still young and my green branches, like those of the spruce, are a lovely sight, summer and winter. It will sadden people if I am chopped down."

The woodcutter took pity on the pine. He came up to a juniper and was about to cut it down but the juniper, too, said in pleading -tones: "Do not kill me, woodcutter! Of all the trees in the forest I am the one to do the most good. I bring good fortune to all and relief to sufferers from a hundred ailments. What will become of the men and animals who come to me for help if I am chopped down?

The woodcutter sat down on a hummock and began to think. "It's really quite a marvel!" said he to himself.

"I never suspected that trees could talk. Now I know that they can, for they have all begged me not to chop them down. What am I to do? My heart is not made of stone that I can withstand their pleas. I would gladly leave the forest empty-handed, but what will my wife say?"

The woodcutter lifted his head and whom should he see coming out of a thicket but a little old man with a long grey beard. The little old man had on a shirt of birch bark and a coat of spruce bark and he came up to the woodcutter and asked:

"Why do you sit here looking so sad? Is it that you ve met with some misfortune?"

"There's no reason for me to be happy," the woodcutter replied. "I came to the forest to chop some wood to take home. But now I cannot do it, such are the marvels I have seen here. The forest is alive and every tree thinks and feels and speaks in a human voice. It breaks my heart when they plead with me. I don't care what happens, I cannot bring myself to chop them down."

The little old man looked at the woodcutter warmly and said:

"Thank you for not having closed your ears to my children's pleas and shed their blood. I am indeed grateful and will repay you for your kindness. From now on you will know good fortune and never lack for firewood, timber or anything else. And that goes for your family, too. Only none of you must be over-greedy if you don't want evil to come of good. Take this rod of gold and treasure it as you would the apple of your eye."

And the little old man gave the woodcutter a golden rod several inches long and no thicker than a knitting needle. "If you want to build a house or put up a barn or a cowhouse," said he, "just go up to an ant-hill and wave the rod three times over it. Be careful not to touch the ant-hill or damage it but tell the ants to build whatever it is you want and it will be ready by morning. And if you are hungry, tell your cooking pot to cook you whatever it is you fancy and it will do it. If it's honey you want, wave the golden rod over a bee-hive, and honey-combs full of fragrant honey will appear on your table. If it is birch or maple syrup you long for, wave the rod over a birch or a maple, and you will have all you want. The alder will give you its milk, and the juniper will make you strong and healthy. And you won't have to hunt or fish either, for your cooking pot will cook you as much meat and fish as you ask for. The spiders will spin you a length of silk or weave you a length of cloth if you only tell them to do it. All this and much more will you have in return for having spared my children. I am the Father of the Forest and I rule over all the trees and wild beasts in it.”

And bidding the woodcutter goodbye, the little old man vanished.

Now, the woodcutter's wife was as ill-tempered and spiteful as a woman can be. Seeing her husband coming toward her empty- handed, she rushed out into the yard in a rage.

"Where is the firewood I sent you for?" cried she.

"In the forest where I left it to grow," the woodcutter replied.

This made the wife angrier still.

"I've a good mind to take a bunch of birch twigs and give you a good hiding, you loafer!" she cried.

But the woodcutter waved his rod without her seeing it and said under his breath: "Let it be my wife and not me who gets the hiding!" And no sooner were the words out of his mouth than his wife started running up and down the yard, gasping and crying:

"Oh! Oh! It hurts! Don't! Please don't!" And she would cover now one, then another part of her body with her hands to shield herself from the dancing, stinging twigs. At last, seeing that she had had enough, the woodcutter ordered the rod to stop.

He knew then how much he had the Father of the Forest to thank for and was very pleased that he could bring his shrew of a wife to reason any time he wanted to. That same day the woodcutter decided to try out his golden rod on some ants. His bam was old and rickety and he needed a new one badly. He went to the forest, and, finding an ant-hill, waved the rod three times over it and said: "Build me a new barn to replace the old one!" And in the morning, when he came out of his house, there in the yard stood a brand-new bam.

From that day there was not a happier man than our woodcutter in the whole of the countryside. He did not have to worry about food, for whatever he fancied the cooking pot cooked for him and served it, too, and all his wife and he had to do was eat it. Between them, they had not a care in the world: the spiders wove their cloth for them, the moles ploughed their fields, and the ants sowed the grain and harvested it when it was ripe. And when the wife had one of her fits of anger, the golden rod brought her to her senses, so that she was the one to suffer most from her own bad temper. Many a husband in our day, I shouldn't wonder, who hears this tale will sigh and say: "Ah, if only I had a rod like that!"

The woodcutter lived to a ripe old age and never knew a day’s unhappiness, for he never asked the rod to do impossible things. Before he died he left the rod to his children, telling them what the Father of the Forest had told him and cautioning them to be careful what they wished for. And the children, who did as he had told them to, lived out their lives as happily as he.

In later years the golden rod passed into the hands of a man who was heedless and unreasonable, thought little of his parents' behest and annoyed the rod with his empty demands. However, as long as what he asked for did not go beyond the bounds of ordinary common sense, nothing bad happened. But one day this foolish man demanded that the sun should come down from the sky and warm his back for him. The golden rod did all it could, but the sun, instead of coming down itself, which was impossible in any case, sent such fierce rays down that the man and his farm were burnt to a cinder and not a trace was left of them. The golden rod, too, melted in the flames or so it was thought, for who was there to say that it hadn't!

Only the trees had been there to see, but the sun's scorching rays had so terrified them that they quite lost the use of their tongues and have remained silent to this day.

Ennemuiste läinud üks mees metsa puid raiuma. Tulnud kase juurde, tahtnud kaske maha raiuda; kask kirvest nähes haledasti paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen alles noor ja hulk lapsi mul taga, kes minu surma pärast nutaksid.“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud tamme juurde; tahtnud tamme maha raiuda. Tamm kirvest nähes haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind veel elama: ma olen alles pisike ja tugev, tõrud küljes kõik toored, mis ei kõlba külvamiseks. Kust tulev põlv tammemestsa peab saama, kui minu tõrud nurja lähevad?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud saarepuu juurde, tahtnud saarepuud maha raiuda. Saarepuu kirvest nähes haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind veel elama! Ma olen noor ja kosisin vast eile nooriku, mis temast vaesest peab saama, kui mind maha raiud?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud vahtrapuu juurde, tahtnud seda maha raiuda. Vahtrapuu aga haledasti vastu paluma :

„Jäta mind veel elama, mul lapsed alles väikesed, kõik kasvatamata, mis neist peab saama, kui mind maha raiutakse?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud lepa juurde, tahtnud leppa maha raiuda. Lepp kirvest nähes haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen parajasti piimas, pean palju väikeseid loomasid oma mahlaga toitma, mis neist peab saama, kui mind maha raiutakse?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud haavapuu juurde, tahtnud teda maha raiuda. Haab aga haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Looja on mind loonud, et lehtedega tuulekõigul pean kahisema ja öösel üleannetuid kurjal teel hirmutama. Mis maailmast peaks saama, kui mind maha raiutakse.“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud toominga juurde, tahtnud toomingat maha raiuda. Toomingas kirvest nähes haledasti paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen alles õitsev ja pean künnilinnule varju andma, et ta minu okste peal laulaks. Kust rahvas kaunist linnulaulu leiaks, kui linnud minu maharaiumise pärast meie maalt ära põgeneksid?“

Mees kuulnud tema palvet ja läinud pihlaka juurde, tahtnud pihlakat maha raiuda. Pihlakas aga haledasti paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen parajalt õilmes, kust marjakobarad peavad kasvama, mis sügisel ja talvel lindudele toitu peavad andma. Mis neist vaestest peab saama, kui mind maha raiutakse?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja jäänud mõtlema: kui lehtpuudest midagi loota ei ole, tahan okaspuiega õnne minna katsuma. Ta läinud kuuse juurde ja tahtnud kuuske maha raiuda. Kuusk kirvest nähes kohe haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen alles noor ja tugev, pean sugu kasvatama, suvel ja talvel rahvale iluks haljendama. Kust nad varjupaika leiaksid, kui mind maha raiutakse?“

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud männi juurde, tahtnud mändi maha raiuda. Mänd aga kirvest nähes haledasti vastu paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen alles noor ja tugev, pean kuusega seltsis ühtepuhku haljendama; kahju oleks, kui mind maha raiutakse.“ –

Mees kuulnud tema palumist ja läinud kadaka juurde, tahtnud kadaka maha raiuda. Kadakas aga haledasti paluma:

„Jäta mind elama! Ma olen kõige suurem metsa varandus ja õnnetooja kõigile, sest et mind 99 tõve vastu võib tarvitada. Mis inimestest ja elajatest peab saama, kui mind maha raiutakse?“ –

Mees istub mätta otsa ja hakkab mõtlema:

„Lugu näitab imelikum kui ime, igal puul oma keel suus ja palumisesõnad keele peal, miska hukkamise vastu seisab; mis pean ma tegema, kui kuskilt enam puud ei leia, mis ennast vaikselt laseks maha raiuda? Minu süda ei jõua nende palumiste vastu seista. Kui mul maist kodu ei oleks, läheksin ma tühja käega koju.“

Seal astub metsa paksust pika halli habemega vanamees, kasetohust särk ja kuusekoorest kuub seljas, mehe ette ja küsib:

„Miks sa, vennike, nii nukral meelel künka otsas istud? Kas sulle keegi pahandust on teinud?“

Mees kostab: „Miks ma nukker ei peaks olema? Võtsin hommiku kirve kätte, läksin metsa, tahtsin sealt tarbepuud raiuda ja koju viia, aga vaata imet! Ühekorraga leian kõik metsa elavalt, kus igal puul oma meel peas ja keel suus on, miska vastu oskab paluda. Minu südames ei ole ühtki verepiiska, mis nende palumise vastu jõuaks seista. Saagu minust mis saab, aga mina ei raatsi elusaid puid hukkama minna“.

Vanataat vahib rõõmsa silmaga tema peale ja ütleb:

„Ma tänan sind, külamees, et sa minu laste palumise vastu oma kõrvu ei olnud lukku pannud; sellest heldusest ei pea sulle kahju tulema; ta tahan sulle selle eest tasuda ja hoolt kanda, et sul edaspidi millestki ei pea puudus olema. Minu laste valamata vere piisad peavad sulle õnneks saama; mitte üksnes ahjukütte ja tarbepuude poolest ei pea sul iial puudust olema, vaid ka muude asjade poolest peab õnnistus sinu majasse astuma, nõnda et sul edaspidi suuremat vaeva ei ole, kui aga südame soovimist suuga avalikuks teha. Siiski pead sa ennast selle eest hoidma, et sinu soovid ülekäte ei lähe; ka oma naisele ja lastele tuleta meelde, kuidas nad üleliigseid soove peavad taltsutama, nõnda et soovimised mitte kõrgemale ei tohi tõusta, kui nende täitmine võimalik näitab. Muidu tuleks oodatud õnnest õnnetus. Säh, võta see kuldvitsake ja hoia teda kui oma hinge!“

Üteldes andis ta mehele paari vaksa pikkuse ja sukavarda jämeduse kuldvitsakese ja lisas õpetuseks peale:

„Tahad sa hoonet ehitada või midagi muud tarvilikku tööd teha, siis mine sipelgapesale, vibuta vitsakest kolm korda pesa poole, aga ära löö mitte pesasse, muidu võiksid väikestele elukatele viga teha. Käsi neile, mis nad peavad tegema, seal leiad sa teisel hommikul töö tehtud, nagu sa olid soovinud. Tahad sa toitu, siis sunni pada, et sa sulle peab valmistama, mis sa himustad. Tahad sa toidu kõrvale maiust, siis näita kuldvitsakest mesilastele ja sunni neid tööle, siis saavad nad sulle rohkem kärjemett tooma, kui sina ja sinu pere jõuaksid süüa. Tahad sa mahla, siis sunni kaske ja vahtrapuud, nad saavad sinu käsku sedamaid täitma. Lepp saab sulle piima andma, kadakas tervist tooma, kui sa neid sedamööda sunnid tegema. Kala- ja liharooga saab sulle pada iga päev keetma, ilma et sul tarvis oleks kedagi elavat looma tapma minna. Tahad sa lõuendit, siid- või villast riiet, siis sunni ämblikke, küll nemad sulle kangast koovad, sedamööda, kuidas sa himustad. Sel viisil ei saa sul edaspidi ühestki asjast puudust olema, vaid igalt poolt küllust, kõik selle eest, et sa minu laste palumisi kuulsid ja neid elama jätsid. Mina olen metsaisa, keda Looja puude üle valitsejaks on seadnud.“

Siis jättis vanataat jumalaga ja kadus sedamaid mehe silmist.

Aga mehel oli kuri naine, kes kui tige koer juba õue peal haukudes vastu tuli, kui ta meest tühja käega metsast nägi tagasi tulevat.

„Kus puud jäid, mis sa pidid tooma?“ kisendas naine; mees kostis tasaselt:

„Jäid metsa kasvama.“

Naine kärgatas vihaga: „Oh oleksid kõik kaseraokesed endid vitsakimbukesteks kokku sidunud ja sinu laisa nahka hakanud parkima!“

Mees vibutas salamahti vitsakest ja ütles, et naine ei kuulnud: „See soovitus sündigu sinule!“

Seal hakkas naine äkitselt kisendama: „Ai, ai! Ai, ai! Oh mis kibe! Ai ai! See käib südamest läbi! Ai, ai! Andke armu!“ Kisendades kargas ta ühest paigast teise, võttis kord siit, kord sealt oma keha küljest kinni, kui oleks kibe vitsahoop sinna puutunud. Kui mees nuhtlusest küllalt arvas olevalt, andis ta vitsakesele sedamööda käsu.

Sellest esimesest katsetööst märkas mees, missuguse kalli ande metsaisa temale oli kinkinud, sest et ta õnnevitsakesest veel naisekaristaja pealekauba saanud. Tal oli vana poollagunenud ait õuel, sellepärast tahtis ta veel selsamal päeval sipelgate hooneehitamise rammu kutsuda; ta läks nende pesale, vibutas kolm korda kuldvitsakest ja hüüdis: „Tehke mulle uus ait õue peale!“ Teisel hommikul magamiselt tõustes leidis ta aida valmis ees.

Kes nüüd õnnelikum võis olla, kui meie mees? Toiduvalmistamise pärast ei olnud neil pisemat muret, mis süda ihaldas ja kuldvitsake leemepajale käskis, seda keetis pada ja kandis iga päev ise lauale, et pererahval suuremat vaeva ei olnud kui – süüa. Ämblikud kudusid neile kangast, mutid kündsid nende põllud ja sipelgad viskasid seemet peale, nõnda kui nemad ka sügisel vilja põllult ära koristasid, nii et kusgil inimese kätt tarvis ei olnud. Pääsesid mõnikord tigeda naise lõualuud lõugutama või mehele midagi kurja soovima, siis pidi ta kuldvitsakese võimul igakord ise kannatama. Mõni mees ohkab vist siin: oh kui mul niisugune kuldvitsake oleks!

Kuldvitsakese peremees oli oma elupäevad õnnelikult õhtule ajanud, sest et tema iial enesele niisuguseid asju ei läinud soovima, mis võimatud näisid olevat. Enne surma andis ta kuldvitsakese oma lastele päranduseks ja õpetas neile, nagu metsaisa teda oli õpetanud, kuidas nad õrna riistakesega pidid ümber käima, ja noomis neid võimatute soovimiste pärast. Lapsed täitsid isa käsku ja elasid niisama õnnelikult kui temagi.

Hiljem kolmandas põlves juhtus, et vitsake mehele päranduseks sai, kes vanemate keelust lugu pidamata väga palju tühja soovis ja sellepärast kuldvitsakest ilmaaegu vaevas; siiski ei tulnud tema soovimistest suuremat kahju, sest et soovitud asjad võimalikud olid. Ülemeelne mees ei leppinud veel sellega, vaid hakkas, vitsa rammu katsudes, võimatuid asju soovima. Nõnda oli ta ühel päeval kuldvitsakest sundinud päikest taevast maha tooma, et tema päikese ligemal olles kord oma selga võiks soendada. Vitsake täitis kül peremehe käsu, nagu teda oli sunnitud, aga et päikese mahatulemine üks võimatu asi on, sellepärast saadeti Looja poolt päikesest nii tulised terad soovija kaela peale, et ta kõigi hoonetega tükkis ära põles ja mitte pisemat märki järele ei jäänud, kus kohas hooned enne olid seisnud. Sellepärast, kui ka õnnevitsake tules sulamata oleks jäänud, ei tea keegi enam paika nimetada või teed sinna juhatada, kust teda otsida sünniks. Arvatakse ka, et mahatulnud ägedad päikeseterad sel õnnetul päeval metsas puud nõnda ära olevat ehmatanud, et nende keelepaelad kinni jäid ja hiljem ükski enam sõna suust ei saanud.

Ancient trees must not be chopped. The one who destroys any ancient trees on a farmstead, will face a loss.

Kes vanu põliseid puid ühest talukohast ära hävitab, see näeb kadu.

Yard trees must not be cut. The yard trees that have been planted must not be cut, or someone will lose a life.

Õue puud, mis on istutatud, ei tohi langetada. Võtab kellegi elu.

Trees are chopped in winter. A tree must be completely dead, only then it is allowed to be chopped. This must be done at the coldest time when it is more resistant.

Puu peab olema täitsa surnud, siis raiuda. Kõige külmemal ajal, siis on vastupidavam.

The Devil may replace a child with a log. Forked logs were not piled in the stack as there was a fear the Devil would replace a child on the farm with such a log.

Kaheharuga puid ei pantud riita, sest kardeti, et vana halv paneb selle tarre lapse asemele.

Violin with a marvellous sound. An exceptional violin with a marvellous sound can be made from a tree chopped on the day all the animals existing on the Earth make a noise.

Puust, mis niisugusel päeval maha raiutud, kus kõik elavad loomad mis maa pääl, häält teevad, saada imeilusa heliga viiul, nagu seda veel enne leitud ei ole.

The herd stick with which a herdsman drove the herd home, had to be put into the eaves of the stable in the evening after coming home, in order to bless the herd.

Karjakepp või vits, millega jüripäeval karjane karja koju ajas, pidi pistetama karja terviseks õhtul koju tulles lauda katuse räästasse.

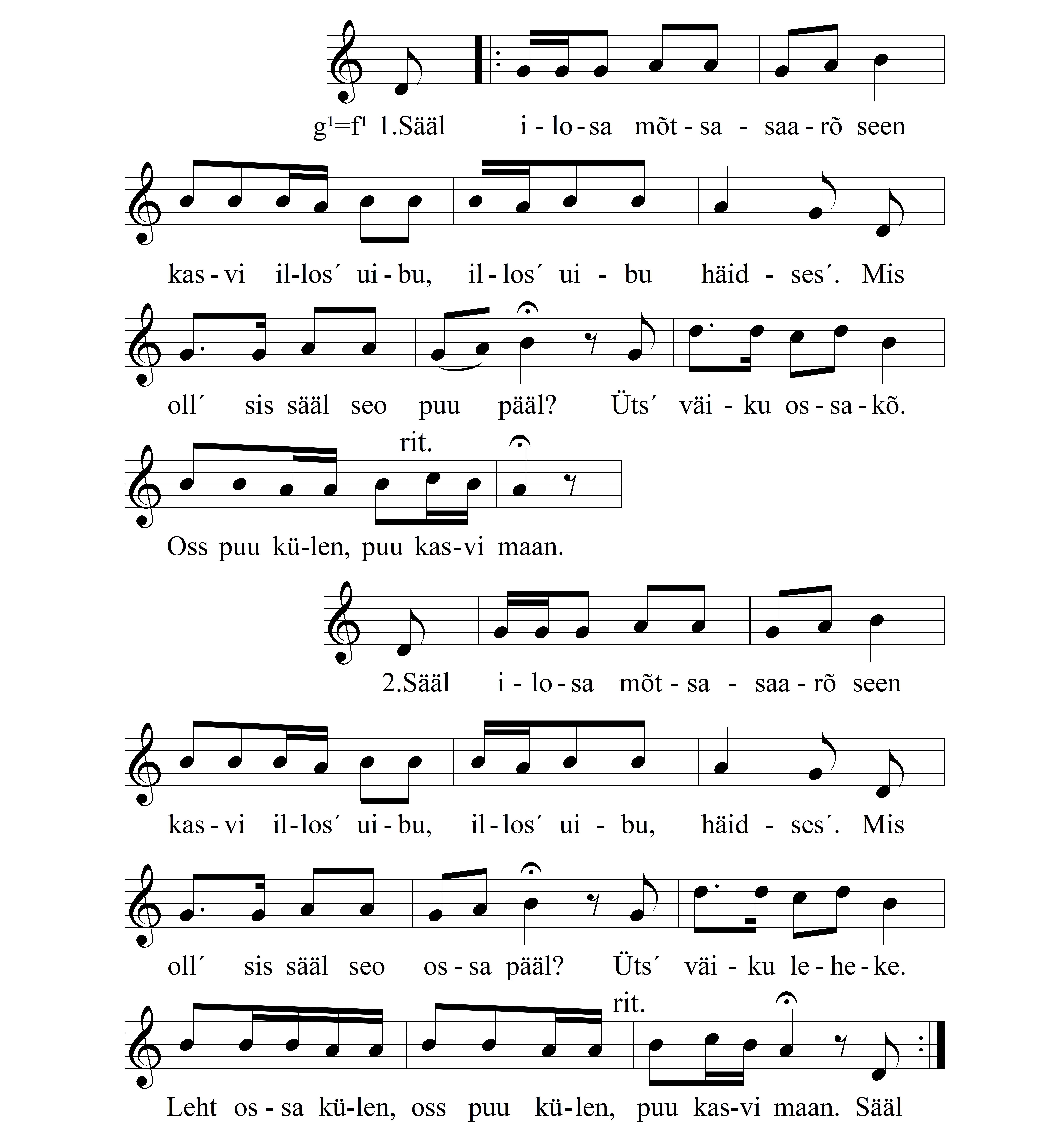

1. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was was on that tree?

One small branch.

A branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

2. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was on that branch?

One small leaf.

A leaf on a branch,

a branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

3. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was on that leaf?

One small nest.

A nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

4. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was inside that nest?

One small egg.

Egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

5. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was inside that egg?

One little bird.

A bird inside an egg,

egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

6. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was in that bird's mouth?

A little song.

A song in the mouth of the bird,

bird inside the egg,

egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

1. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle puu peal?

Üks väike oksake.

Oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

2. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle oksa peal?

Üks väike leheke.

Leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

3. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle lehe peal?

Üks väike pesake.

Pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

4. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle pesa sees?

Üks väike munake.

Muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

5. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle muna sees?

Üks väike linnuke.

Lind muna sees,

muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

6. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle linnu suus?

Üks väike lauluke.

Laul linnu suus,

lind muna sees,

muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Setokeelse laulu laevapuu otsimisest on üleskirjutaja või laulik loovalt mugandanud põhjaeesti laulust, millele osutavad seto keeles võõrad sõnad, nagu kirn, killakuurm, luusima, ning laul on tuntud Põhja-Eestis. Tõlkijale võisid eeskujuks olla selleks ajaks juba trükis ilmunud regilaulud, mille seas on mitu siinse lauluga sarnast, kuid mitte kattuvat varianti (ERl 1926, lk 150–152). Kindlasti pole see esimene kord, kus mõni lauljatest sobitas naabrite laulu kohalikku pärimusse, kuid siinset mugandust ei paista lauljad olevat omaks võtnud. Siiski on tulemuseks ilus poeetiline tekst, mida võib lugeda setokeelse kirjakultuuri hulka.

The writer or singer, who submitted the song text to the Folklore Archives, has creatively adapted a Northern Estonian song about the search for a ship's tree into Seto language. It is likely that the examples used were Estonian folk songs that had already been published in print by that time, (such as in ERl 1926, p. 150–152). While it is not uncommon to adapt songs from neighboring regions into local traditions, this particular song does not appear to have become popular with Seto singers, who have not incorporated it into their oral tradition. Nevertheless, the resulting poetic text is beautiful and can be considered a valuable part of the literary culture of the Seto language.

I got up in the morning,

early before dawn.

I was roaming through the forest,

I was roaming, I was rambling,

I was searching for ship's timber.

Where did I arrive?

I reached a birch tree.

I asked the birch:

"Hail, birch, proud man,

proud white-fur man!

Will you make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail,

underpinning for the anchor?"

The birch just knew how to reply,

how to respond with wisdom:

"I won't make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail,

underpinning for the anchor.

I will become the wheels -

the carts and the sledges,

to roll with the load of spirits

to jostle the train of cargo."

I was roaming through the forest,

I was roaming, I was rambling,

I was searching for ship's timber.

I got into the golden/sweet fir forest.

I began to ask the fir:

"Hail, spruce, tall man,

tall man, high boy!

Will you make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail,

underpinning for the anchor?"

"I was made to be stakes

to be stakes, to be palings,

to harbor the field of braird

to watch the field of grain

to guard the field of oats."

I was roaming through the forest,

I was roaming, I was rambling,

I was searching for ship's timber.

I reached to the wise oak-forest.

I began to ask the oak:

"Hail, oak, low man,

low man, thick man!

Will you make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail,

underpinning for the anchor?'

The oak just knew how to reply,

how to respond with wisdom:

"I won't make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail,

to range over the top of the sea,

to cruise the middle of the sea,

to ply the harbor waters,

to carry the wealth of cargo.

From my timber vats are made,

wheel spokes cut,

runners of sleigh put on,

expensive capes are made,

and nice little chests;

from the stem barrels are made,

from the treetop baby cradles,

from the middle a church,

from the surface milk jugs,

from the bark cream churns,

from the end beer kegs."

Then I came home sadly,

I, sprout, came angrily,

I, darling, went to the apple orchard,

to the merry cherry orchard,

I am floating to the apple tree,

I am rolling to the cherry tree:

"Listen, my busy little apple tree,

my little darling cherry!

Will you make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail?

The branches of the apple tree spoke:

“Yes, I'll make boards for the ship,

boards for the ship, beams for the sail."

Tulin üles hommikul,

vara enne valget,

läksin metsa luusima,

luusima, hulkuma,

laevapuid otsima.

Mille juurde juhtusin?

Kase juurde juhtusin.

Hakkasin kaselt küsima:

„Tere, kask, uhke mees,

uhke valgevatimees!

Kas sust saab ka laevalaudu,

laevalaudu, purjepuid,

ankrule aluspakku?“

Kask mõistis, kohe kostis,

targasti mulle ta kõneles:

„Ei must saa küll laevalaudu,

laevalaudu, purjepuid,

ankrule aluspakku.

Minust tehakse rattapuid1 -

vankriteks1, regedeks

viina-aami veeretajaks,

killakoorma kiigutajaks.“

Läksin metsa luusima,

luusima, hulkuma,

laevapuid otsima.

Sain kuldsesse kuusemetsa.

Hakkasin kuuselt küsima:

„Tere, kuusk, kõrge mees,

kõrge mees, pikk poiss!

Kas saab sinust laevalaudu,

laevalaudu, purjepuid,

ankrule aluspakku?“

„Mind on loodud roikaks,

roikaks ja teibaks,

orasevälja hoidjaks,

viljavälja vahtijaks,

kaeravälja kaitsjaks.“

Läksin metsa luusima,

luusima, hulkuma,

laevapuid otsima.

Sain tarka tammemetsa.

Hakkasin tammelt küsima:

„Tere, tamm, madal mees,

madal mees, jäme mees!

Kas saab sinust laevalaudu,

laevalaudu, purjepuid,

ankrule aluspakku?“

Tamm mõistis, vastu kostis,

targasti mulle ta kõneles:

„Ei must saa neid laevalaudu,

laevalaudu, purjepuid;

ei saa merel sõitjat,

keset merd keerutajat,

linna ligi libisejat,

kalli kauba kandjat.

Minust tehakse tõrsi,

raiutakse rattakodaraid,

pannakse reejalaseid,

tehakse kalleid kapikesi,

kenasid kirstukesi,

tüvest tehakse tündreid,

ladvast lapsehällikesi,

keskpaigast kiriku,

pinnast piimapütte,

koorest koorekirne,

otsast õllepütikesi.“

Siis ma kurvalt koju tulin,

tulin, virves2, vihasena,

läksin, armas, õunaaeda,

lõbusasse kirsiaeda,

Ujun õunapuu juurde,

veeren kirsipuu juurde:

„Kuule, usin, õunapuukene,

lõbus kirsipuukene!

Kas sust saab neid laevapuid,

laevapuid, purjepuid?“

Õunapuu okstest kõneles:

„Jah, must saab neid laevapuid,

laevalaudu, purjepuid.“

1 Originaali ratas võib siin tähendada nii vankrit kui ratast.

2 võrse

Birch will grow and willow will bend.

Küll kask kasvatab ja paju painutab.

Spruce eager to rot, pine fast to soften.

Kuusk kiire kopitama, mänd peagi pehastub.

No birch will grow on a stump of spruce.

Kuusekännu peale ei kasva kunagi kask.

Junipers are breeding twigs, thistles are slave's twigs.

Kadakad on karjavitsad, ohakad on orjavitsad.

All trees were bowing and talking. Animals were also talking. God forbade it, or humans will get smart. However, they still talk twice a year but nobody knows the hour (New Year’s Eve and Saint John’s Day Eve). Trees will not talk because then they could not be chopped and would beg not to be chopped.

Puud kõik kummardasid ja kõnelesid. Loomad ka kõnelesid. Jumal keelas ära, et muidu saavad inimesed targaks. Kaks korda aastas nad siiski kõnelevad, ainult et seda tundi ei tea (uusaastal ja jaanipäeval). Puud ei hakka sellepärast rääkima, et siis ei saaks enam raiuda, sest nad hakkaks paluma, et ärge mind raiuge.

Aspen grew next to Alder. But once they got into an argument.

The Aspen said: "People respect me more than you."

But the Alder objected: "They respect me, not you!"

The Aspen then explained: "I will be made into the best paper, shepherds will make garlands and whisks out of my leaves, but you will become nothing! And what a voice I let out! When I shake myself, everyone in the forest is startled. No one can hear you. My leaves are eaten by all living things, and in winter, they even chew the bark. But nobody wants your bark, and neither do they want your leaves."

The Alder, in turn, praised himself: "I'm still more valuable than you. I will be made into the best mugs and barrels and milk pails. Both women and men like me. I go to town every day, but I never see you. Men come to buy a mug, and they ask if it's made of Alder so that it doesn't swell. Women look for barrels and pails because these do not spoil the flavor. I am also made into spoons and ladles, but you become nothing. The best clothes are dyed with my bark. Women praise that if something is painted with alder bark, it is not afraid of the sun or water and is beautiful for a long time. But you, Aspen, are good for nothing, not for a tool or a vessel. Sometimes no one likes you. If you shake, the people say that the damn Aspen is shaking so bad that it won't let people speak. They don't even want to take you down, you're not fit to burn, and you're not fit for stove wood either."

Aspen argues again: "Oh, how beautiful I am in autumn! There is no one so beautiful. Everyone says: Oh, how beautiful the aspens are! But nobody likes you, the Alder. When the shepherds go through the Alder bush in the fall, they curse your branches because they almost poke their eyes out."

The Alder then said, by way of making peace, that we are both pretty much the same, people like both of us.

Haab kasvas lepaga kõrvuti. Aga ükskord läksid nad vaidlema.

Haab ütles: "Mind austavad inimesed rohkem kui sind."

Aga lepp vaidles vastu: "Mind hoopiski!"

Haab siis seletas: "Minust tehakse kõige paremat paberit, karjused teevad mu lehtedest vanikuid ja vihtu, aga sinust ei saa midagi! Ja millist häält ma veel kuuldavale lasen! Kui ma ennast raputan, siis kõik ehmatavad, kes metsas on. Sind ei kuule keegi. Minu lehti söövad kõik elajad, ja talvel närivad veel koortki. Aga sinu koort ei taha keegi ja lehti ka mitte."

Lepp kiitis jälle ennast: "Ma ikka olen sinust kallim. Minust tehakse kõige paremad kapad ja tõrred ja piimalänikud. Mind sallivad nii naised kui mehed. Ma käin iga päev linnas, aga sind ei näe kunagi. Mehed tulevad kappa ostma, küsivad, kas on lepane, et see ei paisu. Naised otsivad lepaseid tõrdu ja länikuid, et need ei anna maiku. Minust tehakse veel lusikaid ja kulpe, aga sinust ei saa midagi. Minu koorega värvitakse kõige paremaid rõivaid. Naised kiidavad, et kui on lepakoorega värvitud, see ei pelga ei päeva1, ei vett, on vanani ilus. Aga sa, haab, ei kõlba kuhugi, ei ühekski riistapuuks ega anumaks. Sind mõnikord ei salli keegi. Kui sa värised, ütleb rahvas, et pagana haab habiseb nii, et ei lase inimestel kõneldagi. Sind ei taheta mahagi võtta, ei kõlba põletada, no pliidipuuks ka ei kõlba."

Haab jälle vastu: "Oi kui kaunis ma sügisel olen! Kedagi nii ilusat ei ole. Kõik ütlevad: oh missugused ilusad on haavad! Aga sind, leppa, ei salli keegi. Kui sügisel karjused lähevad läbi lepavõsa, siis vannuvad su oksi, et peksavad silmad välja."

Lepp ütles siis lepitades haavale, et me oleme üsna ühesugused mõlemad, inimesed sallivad ikka mõlemaid.

1 päike, päev

A small, low oak tree,

that grew there in the valley.

Refrain: Traa riidi rallalla,

traa riidi rallalla.

Break, break the branches,

don't break the tops.

The treetop becomes the babies' cradles,

the trunks become the girls' beds.

Tammekene madal puu,

mis seal kasvas oru sees.

Refr: Traa riidi rallalla,

traa riidi rallalla.

Murdke, murdke oksakesi,

ärge murdke ladvakesi.

Ladvast saavad laste hällid,

tüvest tütarlaste sängid.