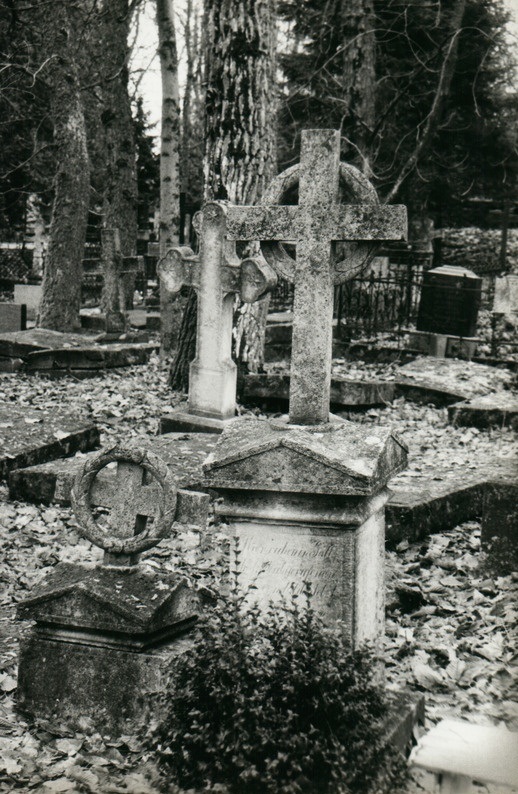

Ancestral spirits/souls

In the olden days, in Tartu County, water was brought to the grave in a bowl so that the dead would have a drink when they came out of the grave.

Vanasti viidud Tartumaal kausiga hauale vett, et surnutel hauast välja tulles oleks juua.

The caretaker of the Kuresaare churchyard (graveyard) went to a wedding in the village of Muratsi, leaving the maid at home to tend to the animals. Suddenly, at dusk, a number of spirits appeared in the room, all asking for water to drink. Because the girl didn't have enough water, the spirits started to strangle the girl. When the host found the maid half-dead on the floor that evening, he realised that there was no water in the troughs at the well for the dead. The troughs at the mortuary well must always be full of water - or the dead will come to strangle those in the room. There must always be a caretaker in the cemetery, who has already been baptized for the dead1, and who can tame the dead in the graveyard and send them to their graves with a blessed staff in hand.

1 Baptism for the dead – a non-biblical practice where a living person is baptized in lieu of a person that passed away.

Kuressaare kerguaidas (surnuaedas) läinud vaht Muratsi külase pulma, ümardaja jäenud koduse loomasid talitama. Korraga, kui videvik käes, ilmunud hulk vaimusid tuppa, kõik küsivad vett juua. Et tüdrukul vett polnud kõige hulga tarvis anda, hakand vaimud tüdrukut käegistama. Kui peremees õhtul ümardaja poolsurnult põrandalt leidis, mõistis ta ära, et kaevul (kajul) künädes vett surnute tarvis polnud. Alati peab surnumajas kajul künad vett täis olema - muidu tulevad surnud tuppa käegistama. Alati peab vaht surmale juba ristitud olema1 ja õnnistud kepiga, mis ta peab käes, aedas surnuid taltsutada ja hauda saata olema.

1 Surmale ristimine – mitteametlik tava ristida keegi elav inimene ristimata surnu asemel.

There is a farm here. The wind broke the old-style building, where the threshing barn and dwelling were housed under the same roof.

In the old days, when it still existed, the master went to thresh at night. He turned on the light and saw that grandfather had come to sleep in the thresh-house. The flail was in his hand and the master threw it on the floor where the grandfather was sleeping. At that time there were no windows yet - there was only a slat covering the hole in the wall. Then the grandfather disappeared with a thump. Who else it was, if not Old Devil.

Siin on üks talu. Tuul lõhkus rehetare ära. Vanasti, kui ta veel alles oli, siis peremees oli läinud öösel rehte peksma. Pannud tule üles ja näinud, et vanaisa on tulnud rehte magama. Terava otsaga ritv oli käes olnud ja peremees visanud selle põrandale, kus vanaisa magas. Sel ajal veel aknaid ei olnud – oli vaid üks laud augu ees. Siis vanaisa kadunud nagu kolksti minema. Aga kes see muu oli kui vanakuri.

In the following song a young girl who has lost her parents visits her mother's grave and implores her to rise up, but is met with insurmountable obstacles. In other variations of the song, the girl visits her mother's (or parents') grave shortly before her wedding and asks for her help in preparing for the ceremony. The song likely reflects ancient wedding customs that involved bridal laments performed to parents. In case of an orphaned bride, lamenting probably occurred at her parents' graves. This particular version of the song begins with a memory of the mother's funeral. The orphan's life was very hard in the village society.

My mother hastened to depart,

to the ground before the rest.

She left me behind, a poor girl,

miserable before my time.

My mother was carried out of the house,

her grace crossed over the threshold.

Mother was taken out of the gate,

her grace stepped over the fence.

Mother was taken along the road,

her grace went along the roadside.

Mother was taken to the funeral,

her grace stepped over the fence.

Mother's grave was being dug,

her grace ran over to her.

Mother was laid in the grave,

her grace fell down into the earth.

"Get up, dear mother,

jump up, my breeder,

come to show us the way,

help us build the path."

"I cannot get up, dear little girl,

nor jump up, dear little hen.

The cross is heavy on my chest,

the barrow is heavy on my hands.

Lilacs sting my eyes,

the chilly leaves pinch my feet."

"If I had known Tooni's house,

known the threshold of Tooni's door,

I'd have brought out my mother,

carried out my breeder.

I'd have made lye in the retting pond,

and black soap in the puddle,

I'd have washed away the stench of the earth,

the stench of death from your mouth,

the stench of the barrow from your hands,

and the stench of the cross from your chest.

I'd have set you to stand by the pole,

stand against the wall."

"Then I'd be called darling,

and named a silver one.

Now I'm called the Devil,

and nicknamed a ground beetle."

1 Tooni – God of Death

Ema ruttas vara ära surra,

enne muid mulda minna,

jättis mu vara vaeseks,

enneaegu armetuks.

Ema viidi tarest välja,

arm astus üle läve.

Ema viidi väravast välja,

arm astus üle aia.

Ema viidi teed mööda,

arm läks teeveert mööda.

Ema viidi matusele,

arm astus üle aia.

Emale hauda kaevati,

arm juurde jooksis.

Ema hauda pandi,

arm alla langes.

"Tõuse üles, emakene,

karga üles, kasvataja.

Tule teed näitama,

radasid rajama."

"Ei või tõusta, tütrekene,

karata, kanakene:

rist on raske rinde peal,

kääbas raske käte peal.

Sirelid pistavad silmi,

jahelehed pitsitavad jalgu."

"Oleks ma tundnud Tooni1 taret,

tundnud Tooni tare läve,

välja oleksin toonud oma ema,

välja kandnud kasvataja.

Oleksin teinud libeda2 leoauku,

lehelise2 musta lombiauku,

maha oleks pesnud maahaisu,

suu juurest surmahaisu,

käte juurest kääpahaisu,

rinde juurest ristihaisu.

Püsti oleks pannud posti toele,

seisma seina najale."

"Tema oleks mind kutsunud kullakeseks,

hüüdnud ka hõbedakeseks.

Nüüd mind kutsutakse kuradiks,

manatakse maajooksikuks."

1Tooni, Kalmu – surmavalla haldjad

2 libe: libeda – ka leheline, pesemiseks kasutatav leeliseline vedelik, tuhavesi

In this song, an orphan girl expresses her desire to invite her parents, who are in the Otherworld, to her wedding. Her brother vows to bring their mother back. He asks her sister to decorate and harness the horse, and plans to take a cloth and socks with him to the cemetery to avoid leaving footprints on the grave. However, the sister expresses her concerns about obstacles such as trees growing on the grave and the guests from the Otherworld being frightened by village dogs, as well as the possibility of having the stench of death. The brother promises to overcome these obstacles by cutting down the trees, tying up the dogs, and making a lye with wild berries to wash away the smell.

The sister then suggests putting more dishes and bread on the table, and supposes that the parents may sometimes visit as an insect or a bird, but realizes that the spirits of the underworld, Tooni and Kalmu, won't allow their mother to return. The rising sun reminds the girl of her mother, and she goes to sleep crying so much that her tears could water the horses.

This song belongs to the "At Mother's Grave" type, too.

[Õde]: "Vellekene, sa armsakane,

[sinult] ma küünitan küsima.

Kuhu mul minna enne [pulmi] kutsuma,

minna pulmasõnumit saatma?

Kuhu ilma mul minna kaema?

Ilmades on mul rohkem omakseid,

kalmus on mul kallimad omaksed,

seal on mu isa hellakene,

kalmus kaks vanemat.“

[Vend]: „Ehi mulle see hiirhall hobune,

kes pole veel rakkes olnud

ega kuu aega kuskil käinud;

kes sõi heinu taevast,

jõi vett vikerkaarest.

Rakenda järele raudsed rattad1

ja vasksed vankrid,

ette pane sa istmed kuldsed.

Siis lähen ma surmavalda kutsuma,

sõmerasse2 sõna viima.“

„Vellekene, armsakane,

võta sa kirves kätte,

seal öeldakse olevat mänd päitsis,

seal on jalakas jalutsis,

haab haua veere peal.“

„[Siis] saab jälle koju mu ema,

kaldub [koju] kaks vanemat.“

„Vellekene, sa armsakane,

keelan ma oma kirstu3 juurde [tulla].“

„Sealt võtan ma liivalinikuid,

võtan kalmusukki,

liiva teen ma tee linikulise,

kalmule teen ma tee sukalise.

Siia ma ei pelga jälgi jäävat,

ei pelga ma sammu [maale] saavat.“

„Aga kui nad ei tohi koju tulla,

aga kui pelgavad küla koeri,

varjavad end valla kutsikate eest?“

„Siis panen kinni küla koerad,

panen valla Harmid ahelatesse.“

„Vennakene, vaid seda õudust nad kardavad,

et on juures maahais,

kui ligi ka liivahais,

kaela juures kalmuhais.“

„Ma teen ühe libeda4 liua sisse,

sooja vee lännikusse,

ma teen ühe libeda5 lillakase,

teise teen ma maasikmarjalise,

kolmanda kuremarjalise6.

Siis pesen su juurest maahaisu,

kaela juurest kalmuhaisu.“

„Vennakene, armsakane,

siis pane sa liud laua peale,

lisalusikas liua veere pääle,

lõika lisa-leivaviilukene,

pane lisapeeker suitsuaugu peale.“

„Kõik mu omaksed on näljas,

kõik mu sugu on end korda seadnud;

pole mul kahte omast,

ühte pole ema hellakest,

kaol kahte vanemat.“

„Aga kui nad lendavad liua veere peale,

[kui ta] tuleb peekri põhja peale,

koju ta lendab liblikana,

kodu ta käib kärbsena?“

„Kes on tuvi tulba otsas,

kull tare harja peal –

see on minu emakene,

need on kao kaks vanemat.“

„Aga kui ta kaeb räästast

või vaatab varju alt?“

„Tooni7 ei lase tal koju tulla,

Kalmu ei lase tal koju tulla.“

„Kui ma nägin päikest (päeva) tõusvat,

aoserva astuvat,

mõtlesin oma ema tulevat.“

Siis läks ta mari magama,

läks ta osi unevoodile,

nuttis kümme vett külje alla,

nuttis seitse vett selja alla,

küllalt oleks sest saanud hobuseid joota,

küllalt varssadele valada.

1 ratas – tähendab ka vanker

2 jäme liiv, kasutatakse sageli itkudes haua metafoorina

3 Neiu mõtleb siin arvatavasti oma veimekirstu või riidekirstu.

4 libe: libeda – ka leheline, pesemiseks kasutatav leeliseline vedelik, tuhavesi

5 lillakas – ka linnumari, liimukas, võro k linohk

6 kuremari – jõhvikas

7Tooni, Kalmu – surmavalla haldjad