Nature and human in folklore

Estonian peasantry folklore embodied the knowledge and skills necessary for a life in close proximity to nature, as well as for entertainment and mental wellbeing. Estonian older folklore and customs developed in close connection with everyday rural life and work. Preserving the basics of life was considered important – nature's favour and fertility; family and harvest growth; a strong community and a connection with ancestors.

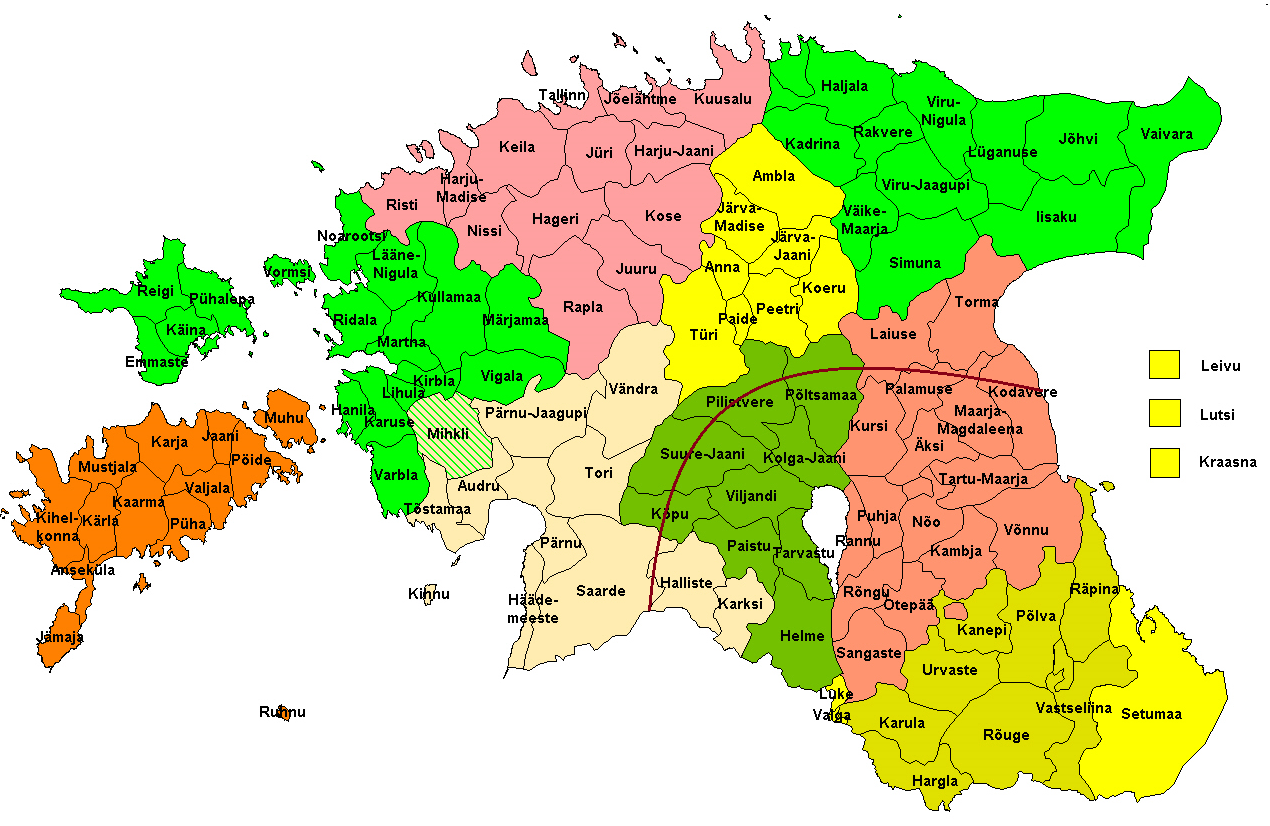

The Nature Folklore website includes ancient folk songs regilaul (or runolaul), magic spells, tales, riddles, proverbs, beliefs and folk wisdom from the Estonian Folklore Archives of the Estonian Literary Museum. In addition to the texts, melody notations, pictures, audio and video recordings, as well as theoretical approaches and references will be published. Our framework project, the European Capital of Culture 2024, covers Tartu and Southern Estonia, therefore we will publish first the material pertaining to this area. In order to give a more complete picture of Estonian folklore and enable some comparison, we also add some texts from Northern and Western areas. The website is currently still under development and is constantly being updated.

Estonian folklore primarily reflects the tradition of the last few centuries, but has also preserved much older, pre-Christian layers, including ancient mythical motives. The tradition as we know it today from written and oral sources, evolved its character from the local population, immigrants and neighboring peoples. The first settlers arrived to Estonian area after the end of the glacial era; and they were most likely followed by several more waves of immigration. Since the first millennium the ancestors of Estonians had been sedentary farmers, while they also continued to hunt, fish and gather. In Estonian folklore, a broadly animistic worldview became mixed with Christianity, which was vigorously spread by the Northern Crusades from the 13th century onwards.

There was no rigidly defined border between people and other nature beings: they were inhabitants of one world in which their lives depended on each other. Nature was somewhat unpredictable and powerful, and it was better to get along well with it; for which purpose the necessary experiences and practices were mediated by tradition. The well-known proverb "the forest has the eyes, the sea has the ears" conveys the idea that the world watches a humans both in their relationship to people and to the other creatures of nature. A person who acted correctly could receive an unexpected gift, but a violator of unwritten customs could be hit by a change of "rules of the game" – for example, he could lose his way home or even turn into an animal.

The experiences thus gained were passed on to subsequent generations. This is how the voices of people from the past, as well as the voice of nature – as they interpreted it, speaks within folklore. Nature spoke to man through its representatives – fairies and spirits, supernatural animals and birds, and more indirectly through omens and meaningful events.

Every culture develops it’s understanding of nature and of the relationship between man and nature, which is based on direct experience and cultural tradition. Intangible heritage does not reflect reality directly, but selectively and poetically. A faith in nature spirits does not necessarily indicate simplicity, but can instead carry a message about the living aspect of nature. It might advise, for example, that communication with the living requires care and caution.

Although not all of the ancestors' actions in nature were equally agreeable in today's terms, folklore reveals a reverence for nature. Inevitably, life as hunters or cattle-breeders in the North meant killing animals for food and goods. It is possible that when considering the wellbeing of nature, it was not so much the individual being that was meant as the "community" of nature - just as for people, the welfare of the human community was of primary importance.

Primitive hunting methods may have been cruel to individuals, but alongside there existed an effort to preserve nature, whose fertility and favour were not taken for granted. In addition, the society was not completely uniform, – at any time there would have better and worse people, and the messages that have reached the archives reflect the reality in all its contradictions.

Stories, songs, beliefs and rituals suggest that the relationship between nature and human communities functioned as a kind of contract where people considered their share and responsibilities. Humanity probably felt itself as one of many other living beings, not as a king or a ruler. Everyone had a similar goal: the continuation of life on the Earth, where the humans also tried to contribute from their side – to keep the sources of heat and light moving, forests and lands fertile. Even if several beliefs or rituals taken one by one may not seem rational, or with visible consequences today, they were part of the more general way of living and thinking, where juxtaposed with directly practical actions there were activities of symbolic value to shape the attitudes and culture.

Initially Estonian oral tradition was collected by the Baltic German literati, and since the mid-19th century by native Estonian folklorists and volunteers. Together with some older records (in travelogues, court records etc.), the materials form a unique collection of Estonian folklore, in which the regions with their local identity, such as South, North and West Estonia, are clearly distinguishable. The folklore collection is kept and replenished since 1927 in the Estonian Folklore Archive of the Estonian Literature Museum in Tartu.

Knowledge and inspiration for interpreting Estonian nature folklore have been given to us by Estonian folklorists Mattias Johann Eisen, Oskar Loorits, Ivar Paulson, Uku Masing, as well the colleagues at the Estonian Literary Museum: Mall Hiiemäe, Risto Järv, Astrid Tuisk, Janika Oras, Aado Lintrop, Mari-Ann Remmel, Mare Kõiva, Mare Kalda, Eda Kalmre; and at the University of Tartu professor Ülo Valk and many others.

South Estonian is spoken in south-eastern Estonia, encompassing the Tartu, Mulgi, Võro and Seto varieties. In the reference of each folklore piece on the website, the place of its origin is indicated with the abbreviations khk, v, p (kihelkond 'parish'; vald 'municipality', küla 'village').