Mäetagused vol. 63

Summary

-

National cultural festivals as part of the world’s cultural heritage

National cultural festivals as part of the world’s cultural heritage

Iivi Zajedova

Keywords: festivals, folk dance, hobby activities, tradition

The tradition of Estonians’ cultural festivals is a rich topic and may be considered profoundly distinctive for Estonian people. It is a unique way of maintaining and advancing the traditions of national heritage through a variety of activities. Since after World War II a forced separation took place in Estonian national culture and many citizens of the former Republic of Estonia escaped from the Soviet occupation to the Free World (thereby splitting geographically into the groups of homeland Estonians and Estonians abroad), the tradition of cultural festivals continued on both sides of the Iron Curtain, in an effort to maintain traditions under different circumstances. This special issue of the journal is the outcome of a project begun in 2012, to investigate the role of folk dance hobby activities and festival traditions in the maintenance of national culture. During the compilation of the special issue the focus shifted towards the question of the role of Estonians’ traditional festivals in the ever-changing world – their viability and transmission of the traditions of national identity both in Estonia and abroad. This issue covers the experiences of hobbyists in traditional cultural activities, their involvement in festivals, and their cultural contribution, both in Estonia and in communities outside it. Among the basic themes of the articles the following deserve special attention: the place of the Baltic countries’ song festivals in the world cultural heritage and the relationship between new and traditional songs; the role of dance festivals in the preservation and transmission of traditional dancing skills in contemporary Estonia and the nature of cultural heritage being maintained at dance festivals; the role of folk dance among the Skolt Saami, our neighbours in the North, in shaping their history, identity, and future, as well as the connections between contemporary Skolt Saami folk dance and identity; the revitalisation of old folk musical instrument traditions both in Estonia and among the Estonian diaspora; the split and repression in the realm of choir music, due to the forced separation by a foreign power; the recording of World War II refugees’ cultural events on narrow gauge film in Sweden and the identification of the filmed individuals by a group of experts. Another and not less important goal of this issue is to stimulate a more wide-ranging discussion in Estonian society about the role of hobbies and traditional festivals, especially outside Estonia, which are an integral part of Estonian national culture and Estonian folk culture.

-

-

Traditions and heritage of Baltic song celebrations

Guntis Šmidchens

Keywords: heritage, song celebrations, songs, tradition

An overview of all the 1,973 songs that have appeared in seventy Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian national song celebration programmes from 1869 to the present day reveals a richly innovative, creative tradition: in each of the three festival repertoires, 74–84 percent of the songs were performed only once over the entire history of the national celebrations. When concert participants choose to repeat songs sung in previous years, they identify these songs as heritage. Sometimes, most notably in the retrospective Estonian programmes of 1969 and 2014, a large portion of the concert repertoire was repeated from the past. The tradition as a whole, however, is not necessarily past-oriented. Some celebrations have turned away from heritage. In the 1928 Estonian celebration, for example, only 2 percent of the programme (only one song) had ever been sung in an earlier celebration. This, too, is a heritage of song celebrations: future organisers are free to decide how many, if any, songs they wish to repeat from earlier festivals. The song festival tradition allows both innovative and conservative choice of repertoire at any given festival.

-

-

What kind of Estonian culture is fostered at dance celebrations?

Sille Kapper

Keywords: agency, dance celebration, dance world, folk dance as a hobby, traditional dancing

Estonian Song and Dance Celebrations take place every five years, involve thousands of participants and great audiences in venues or via the media. In Estonia the tradition of dance celebrations as well as (stage) folk dance in hobby groups dates back to the beginning of the twentieth century. In the learning processes and programmes of dance celebrations traditional folk dance is used in the format of some single elements or features only.

In a situation like this it is important to ask what role dance celebrations play in preserving and passing on the knowledge and skills connected with traditional dancing in contemporary Estonia. Which concepts and realisations of a dance may be compatible with the process of dance celebrations, and which of them are left aside and why? The article is based on the author’s dance ethnography (2008–2105) in two dance worlds, which partially overlap each other: it is the traditional folk dancing on the one hand, and the (stage) folk dance as a hobby, including participation in dance celebrations, on the other.

The study shows that it is ourselves who create those institutional truth regimes that promote certain ideas while overshadowing alternative knowledge, although important for the preservation and sustainable development of our national culture. The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

Dance celebrations do not support the propagation of the plural and diverse nature of traditional culture (on the example of traditional dancing) because their principal output, the massive productions, are not designed for that purpose, have other strengths and also other requirements in connection with its specialty to address large crowds at rather long distances. The format of dance celebration suits well for highlighting the positive, unified, and common values of national culture, while social criticism is not an attitude readily adopted, either by participant dancers or by the audience, even if such an approach is proposed by a creative team. Although the agency of the lived body as a source of knowledge can generally be well utilised in increasing one’s self-awareness in dancing, the dance celebration processes do not enhance the personal agency of participant dancers – most choices are made by the artistic teams and group leaders while the dancers’ main task is to obey the rules. This could be seen as a point of concern because low agency, meaning here unwillingness and poor ability to make intended decisions, may easily lead to alienation from the values important for the tradition of dance celebration itself and Estonian national culture as a whole.

-

-

Identity and agency in contemporary Skolt Sámi folk dance

Identity and agency in contemporary Skolt Sámi folk dance

Petri Hoppu

Keywords: agency, culture, folk dance, identity, Skolt Sámi

This article examines the role of dance of the Skolt Sámi in Finland in negotiating their history, identity and agency. The Skolt Sámi are a culturally and linguistically distinct group of the Eastern Sámi. Originally, they lived in a wide area, from Lake Inari eastward to the Russian city of Murmansk. Today, most Skolts live near Lake Inari in Finnish Lapland, where they were relocated after World War II. The multiple identities of the Skolts are actualized in many ways, in language, music, religion, but perhaps most distinctively in their dancing. Their dancing traditions, especially the quadrille, separate them from other Sámi in Finland and connect them to Northern Russian culture. Despite their dramatic past, the Skolts have preserved their culture and distinctive, yet ever-changing ethnic identities. Their identities are characterized by many points in their social and personal histories, and dancing is a part of the routes they have traveled within these experiences.

-

-

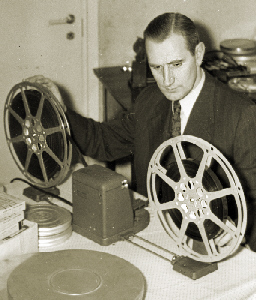

Film clip as a document of cultural history: The case of Hindås

Film clip as a document of cultural history: The case of Hindås

Triinu Ojamaa

Keywords: film clip, Estonians Swedes, refugee life, song festival, summer fest

At the end of the 1940s, a viable Estonian exile community was formed in Sweden; it mainly consisted of the World War II refugees. During the first two decades, an amateur film maker, Harald Perten, recorded the most important events of the Estonian Swedes (i.e. Estonians living in Sweden). He produced some longer silent films which chronicled life in exile. The films contain subtitles with the name of the event as well as some other data. Yet, a large part of his recordings stayed unexploited. The “raw material” belongs to the Estonian Archives in Sweden and presently the concrete data about those clips are missing, i.e., it is unclear when and where Perten filmed those clips. Based on a clip of such kind (working title “Hindås 19??”), the current article describes the course of identification of the filmed cultural event and people participating in it.

The study was designed as a two-step analysis:

- The analysis of the film clip Perten supposedly made at an exile Estonians’ summer fest. A group that consisted of eight Estonian-Swedish experts (they had participated in the cultural life of their diaspora group since the end of the war) watched the clip with an aim to identify from memory the people and the event. They were successful in identifying the former – the prominent Estonian-Swedish cultural and political figures. The question whether the clip had been filmed at the end of the 1940s or at the beginning of the 1950s caused disagreement among the experts.

- The analysis of the print sources was based on the exile Estonian newspapers and summer fest booklets. It became apparent that the Hindås summer fest, which merged St. John’s Day with the national Victory Day and a small song festival, took place in 1947. Alas, at the same time, Estonian Swedes celebrated the fest in eight different regions all over Sweden. According to the newspaper articles and booklets, some people identified in the Hindås clip actually took part in different summer fests.

In the course of the analysis, the year of the filmed event remained unclear. For different reasons, we cannot be sure whether this event actually took place in Hindås. While discussing the cultural-historical value of the unidentified film clips, we can say that even if we do not know the exact data, those clips nevertheless can be regarded as a unique source that demonstrates the cultural life of a well-organised exile community as well as the early cultural contacts with the representatives of the host country.

The Hindås clip with subtitles is available on the Internet at http://www.folklore.ee/tagused/nr63/.

-

-

Preservation of folk instrument heritage in Estonia and abroad

Preservation of folk instrument heritage in Estonia and abroad

Ain Haas

Keywords: bagpipe, bowed lyre, Estonian kannel

By the middle of the 20th century, old folk musical instruments had disappeared from Estonian culture. Musicians played modern internationally widespread instruments, especially the accordion and the guitar. The article discusses the return of old folk musical instruments, especially the Estonian kannel (plucked Baltic psaltery), bagpipe, and bowed lyre. The revival of these traditions has been more marked in Estonia, due to the contribution from music schools and museums; yet similar processes can also be detected among diaspora Estonians. Initiators and key persons enthused by the lost culture of their ancestors have played an important role on both sides. Interest in these old instruments is a manifestation of people’s resistance to the homogeneity of the modern society.

Urbanization, international contacts, and modern technology led to the fading popularity of folk music in the past century, yet the same factors have recently proven important in reviving traditions.

-

-

Split in Estonian choir singing in the Soviet period

Hain Rebas

Keywords: Estonian diaspora, Gustav Ernesaks, Harri Kiisk, Juhan Aavik, Roman Toi, song festival

In Estonia the notion of Estonian song festivals has become synonymous with the name of beloved composer and conductor Gustav Ernesaks (1908–2003). The reasons for this are both unplanned and purposeful, both simple and complex.

In marked contrast, the song festivals are not even peripherally associated with the traditions and conductors outside of Soviet-occupied Estonia, who were in many ways the custodians of qualified and non-Sovietised Estonian choir music. Prominent figures such as Juhan Aavik, Eduard Tubin, and Tuudur Vettik, followed by their students Harri Kiisk in Sweden and Roman Toi in Canada, promoted the democratic and freedom-oriented Estonian Song Festival tradition in Sweden, Germany, Canada, and the US for half a century and from 1972 onwards also in transnational ESTO festivals.

It is generally maintained that the Estonian diaspora played a distinctive role in the dismantling of Soviet rule in Estonia a quarter-century ago. Consequently, we must accept that song festivals held outside of Estonia effectively kept the spirit of a free Estonia alive. It is therefore time to harmonise the Ernesaks’ excluding phenomenon pertaining to song festivals since World War II with the efforts of Estonian master conductors in Germany, Sweden, Canada, and the US. Their accomplishments far away in the Free World added significantly to the present-day song festival tradition that grows ever stronger in Estonia. It is compellingly clear that the Estonian diaspora song and ESTO festivals should be included in the Estonian paragraph of the 2003 UNESCO World Heritage List.

And, if one looks around on the Song Festival Grounds in Tallinn, one easily discovers space enough for Dr Roman Toi of Toronto (b. 1916) beside the statue of Maestro Gustav Ernesaks.

News, overviews

-

In memoriam

Heikki Silvet

March 10, 1942 – December 11, 2015.

Anna-Leena Siikala

January 1, 1943 – February 28, 2016.

The editorial board commemorates the former colleagues.

-

-

Sixth Estonian language seminar for kindergarten teachers in Tartu

Piret Voolaid writes about the training seminar on the Estonian language for kindergarten teachers, which was organised by the Estonian Literary Museum in Tartu on December 3 and 4, 2015.

-

-

Folklore collection at the Estonian Folklore Archives in 2015 and President’s folklore collection awards

Folklore collection at the Estonian Folklore Archives in 2015 and President’s folklore collection awards

On March 28, President Toomas Hendrik Ilves handed out President’s folklore collection awards to the best folklore collectors of 2015 at the Estonian Literary Museum in Tartu. Prior to this, the Estonian Folklore Archives assembled their contributors to summarise the last year’s achievements and make plans for the coming year. An overview of these events is given by Astrid Tuisk.

-

-

Calendar

A brief summary of the events of Estonian folklorists from July 2015 to December 2015.

-

-

Monograph about the relations between a foreign corporation and the local community.

Welker, Marina. Enacting the Corporation. An American Mining Firm in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Berkeley & Los Angeles & London: University of California Press. 2014. xviii + 289 pp.

An overview by Vladimir Poddubikov.

-

-

Another publication of Udmurt folksongs

Irina Pchelovodova & Nikolai Anisimov. Lymshor pal udmurt"eslen kyrӟan gur"essy / Pesni iuzhnykh udmurtov / Songs of Southern Udmurts. Izhevsk–Tartu, 2015. 374 pp.

An overview by Madis Arukask.

-