Anneli Porri

Pop art, which emerged in the UK and the United States in the 1960s, depicted media objects, mundane daily life and consumer goods. Many have agreed that the critical turn in pop art is marked by the 1956 collage "Just What Is It that Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?" by Richard Hamilton. In this collage the artist combined materials advertising various consumer goods, comic strips and interior design. By the end of the 1960s, pop art as a visual style also emerged in the creative works of Estonian artists and designers. The first elements appear in the creation of the group of artists Visarid; authentic pop elements are also used by the artists of SOUP 69. The article observes the mundane banality of life in the Soviet Estonia and how and whether it is expressed in fine arts by means of pop art.

Opportunities for working with the visual style after a long period of cultural and political isolation came with what was called "Khrushchev's thaw". During this period the exchange of information with the Western world improved considerably; in 1965 the sea route between Helsinki and Tallinn was reopened after twenty five years. Also, the Estonians living in the Northern part of the country could expand their horizons by watching the Finnish television.

In Great Britain and America, pop art shocked people accustomed to versatile living environment by transgressing the line between good taste and bad taste. Until then art aimed to counterbalance the routine and mundaneness of everyday life, providing the artists an aesthetic oasis and keeping the circle of literati with good taste closed. In the Soviet Union this kind of critique was inconceivable, since pop art promoted what people lacked in daily life. The Soviet planning economy was unable to supply the population with commodities, which led to a strong fetishising of the western goods. This led to the gradual construction of an identity that was based on being opposed to everything Soviet, and was expressed in the attempt to imitate westerners in both behaviour and clothing.

Proceeding from the aesthetics and the choice of topics, pop art could be unmistakably associated with the Western society and was therefore publicly condemned. Still, people found ways to put the alluring visual language into proper use: the one-dimensional and transparent aesthetics of pop art was most convenient to apply in the so-called small media: areas of art that remained in the periphery outside the art hierarchy, depicting, among other things, objects characteristic particularly of pop art. Theatre design (Leonhard Lapin), illustrations for youth magazines (Ando Keskküla, Andres Tolts) and animated cartoons (L. Lapin, A. Keskküla, Rein Tammik) were the most suitable and extensive sublimation channels for talented designers and architects.

An interior design magazine Kunst ja kodu, or Art and Home, which was published in Estonia but circulated all over the Soviet Union, often applied the visual language of pop art in its designs. Kunst ja kodu represented an avant-garde achievement, reproducing the creation of consumer artists or offering tips for interior decoration on photos, i.e. the work was not created in the form of an assemblage, object or painting, but the image characteristic of pop art was obtained in the form of a photo reproduction accompanying the article as an illustrative means. Even more progressive compared to the magazine Kunst ja kodu was the youth magazine Noorus, or Youth, which published illustrations by both the initiators of the group SOUP 69 and members of Visarid. Owing to these two magazines it is possible to talk about repro pop in the Estonian context.

In their works the artists employed abstract rather than material values, symbols and allegory rather than clearly outlined icons. The most explicit images of the period were bus tickets, tetrahedral milk cartons, vacuum cleaners, pillows and canned soup. In Estonia, pop art did not serve to reflect the surrounding life. Regardless of the claims by members of Visarid and SOUP 69, pop art in the Soviet Estonia attempted to discuss the same objects using the language that was used in the Western world. A clear reference to this is the poster of a soup can designed by L. Lapin for the first SOUP 69 exhibition in the Pegasus café. The can, borrowed from Andy Warhol, is opened, with a spoon approaching from the top, perhaps to empty its contents. It seems that in this context the young artists opened the can to get in there, and finally see all the things that are discussed in magazines of visual art on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Riina Kübarsepp

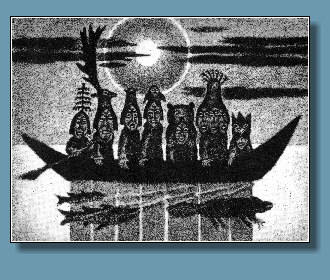

Kaljo Põllu (born in 1934) entered the Estonian art and art circles in

1962 when he became the head of the art cabinet at the University of Tartu

with a diploma in glass art. Initially, he figured in the Pallas-like art circles

of Tartu as an ambassador of the art fostered in Tallinn, bringing the

wafts of avant-garde to the university town and being involved mainly in op,

pop and modern art. In 1967 the group of artists

Visarid was founded on his initiative. In 1973 when the art cabinet, which had turned into an

interdisciplinary school of thought, was moved from the adjacency of the University main building to Tiigi Street and had lost its significance as

the intellectual centre, Põllu left for Tallinn, where his creative

signature changed considerably. Already in Tartu he had established contacts

with scholars of Finno-Ugric studies, and he had participated in expeditions

to the Estonian kinsfolk. During his Tallinn period, the artist focused in

his works on the search for Finno-Ugric roots. The uniqueness of his series

of graphic art won Kaljo Põllu repute not only in Estonia but also in the

art circles of the entire Nordic area (and perhaps elsewhere).

The article opens with posing the question about the turning points in Kaljo Põllu's creative work, where an innovative avant-garde of the late 1960s Estonian art became a Finno-Ugrian and visualiser of the Finno-Ugric mythology. In order to describe the art and cultural phenomena and the political situation during the "thaw" of the late 1960s, the first part of the article presents an introductory overview relying on theories formulated by Jaak Kangilaski, forming a framework on which further discussion is based on.

Several chapters of the article emphasise the critical and decisive impact of the events of 1968 in Europe and America on Kalju Põllu from the aspect of temporal concept.

The overview discussing the different angles of Põllu's creation is essay-like in form, aiming to present various models and approaches to interpret his works. The article also explicates certain key words, like Nativism and globalisation, which are essential for an adequate overview of the topic.

Kalju Põllu was the founder of the Visarid group in 1966, and, incidentally, also the person who ended its activities in 1972. The radical turn into the Finno-Ugric themes in his works may be thus considered as concurrent with the end of the Visarid group.

Already during the art group period Põllu communicated actively with Paul Ariste, Jaan Eilart and Jaan Kaplinski, who, consequently, guided his creative work by writings introducing the Finno-Ugric worldview. Being familiar with the Finno-Ugric worldview is therefore essential in understanding and conceptualising Põllu's Finno-Ugric work.

Among the reasons underlying the so-called creative rebirth of many Estonian artists are the end of the "thaw", the Iron Curtain becoming even more impenetrable, and the culmination of social stagnation. The period 1976-1986 is characteristic in the weakening of the avant-garde ideology owing to the increasing importance of National-Conservative philosophy, which identified itself with the traditions of aesthetics. Like other leading avant-garde authors (such as, for example, Tõnis Vint), Kaljo Põllu saw the return to the ancient mythology as a way to preserve his creative independence during the 1970s' stagnation. Revolutionary ideas and adaptation became intricately interwoven in the personality of this Soviet artist.

Thus, Kalju Põllu can be characterised by an ability to integrate, which is common to Estonian artists in general, intellectual brilliance, strong character and creative independence. But his creation is remarkable in the interrelation of modern art and the art based on ethnic roots.

Sigrid Saarep

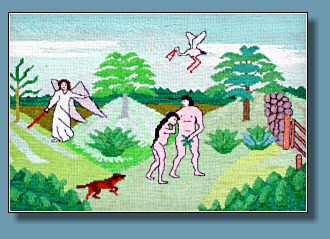

A new field of visual folk art has emerged in contemporary Estonian folk art - namely, a symbiotic third coming of folk art, which has developed as a fusion of visual tradition characteristic of professional art and ethnic worldview and handicraft skills. Modern creators of visual folk art are unique artists of lore, who differ from earlier handicraftsmen in the subjective original creation, which does not serve practical purposes.

Folk art has developed simultaneously with tendencies in

academic art. Closer contacts between urban and rural population since the

18th-19th century contributed to the acceleration of the mergence of

popular and elitist art forms. This period introduced several forms of the

second wave of folklore, such as lubok (ethnic wood engraving in the

Slavonic areas) or limner paintings (untrained painters in America), Naivist

paintings, propaganda ceramics of the French Revolution, hand-painted

signboards of stores and the painted backgrounds in photo studios.

Professional national art emerged in Estonia as late as in the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. This explains the rather late contact of the Estonian agrarian population with "pictures" and academic art tradition. By 1906, when the works of artists "proper" were displayed next to amateurs and handicraftsmen at the annual exhibition of the Tartu Farmers' Society, it can be said that the tradition of painting had reached the agrarian population.

The last decades have witnessed an increased interest in non-elitist forms of art. Various terms and definitions are applied to the amateur art standing outside the academic tradition. In the United States, this trend is referred to as contemporary (visual) folk art, which includes Naivism, outsider art, rural handicraft. In Finland, the creation of village artists is called by the abbreviation ITE (in Finnish, Itse Tehty Elämä, or `Self-created Life). Other popular terms are hobby art and the term `village fool', which obviously defines an artist's creative activities as `madness' or `foolishness'.

The institutional sphere of Estonian folk art has thus far avoided recognising the tradition of visual folk art in the context of our folk culture. The terms applied here are amateur performances, home decoration and hobbies, but original ethnic creation of high quality which stands head and shoulders above hobby activities is ignored.

Still, even the Estonian folk art knows village geniuses like Jaan Uba, Harri Aer, Leida Alliksaar, Adelbert Juks, Aleksander Tarvis and others, who usually remain outside the institutional system and support of folk culture. But their uniquely enchanting creation appeals to both the general public and experts in the field.

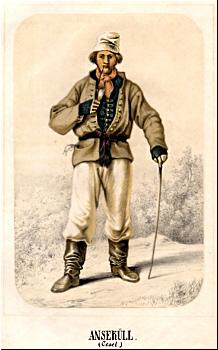

Kadri Viires

The article overviews drawings and characteristic features of documental drawing in the Estonian ethnographic material. This is an area that has been related to the activities of artists in collecting and recording folk culture.

In recording the early visual material about Estonia in the

17th-18th century travelogues or reference books and the newer 19th century

Balto-German agrarian culture, the line between works of arts and

documentary illustrations is vague: the visual material is used as a source in

studies into both art and ethnology.

The enlivening of folklore collection in the late 19th century and early 20th century brought along the documenting of material culture in the form of drawings. A number of artists and art students partook in the collection work initiated in 1909 by the Estonian National Museum. Material relevant to folk art, that could not be stored in the museum, was recorded in the course of collection campaigns. Photographing technology of the time had limited technical resources and availability.

At the beginning of the 20th century a separate archive of drawings was established at the Estonian National Museum; ethnographic drawings became a part of the systematised recording of material culture and were in concordance with the museum's collection principles. The criteria for the collected visual material of the time in recording information are, for the most part, valid even now.

During the post-WWII period, the studying of ethnic material proved an alternative in counterbalancing the official ideology. Collection, recording and use of folk art in creative work clearly represented the spirit of national self-expression. Documenting folk art increasingly became a part of art instruction, as an important prerequisite of an ethnographic drawing is good knowledge of technological idiosyncrasies and details of construction of the represented object material. A detailed drawing of an object is the most important and effective way of exploring the nature of the object.

Modern photography enables to record the material and spiritual context quickly and objectively, or so it seems, but similarly to drawing, it also entails the subjective aspect of the person taking the photo. A photograph does not provide sufficient parameters (such as, e.g. structures, cross-sections, scheme, fixed colour solutions, etc.) for describing/ documenting the object under study. Both ways of documenting may be considered separate forms of producing visual information, which cannot be considered conflicting.

Riina Tomberg

The article overviews the tradition of knitted sweaters worn on the islands off the western coast of Estonia during the period from the 1880s to the 1920s-1930s. The article discusses the knitted sweaters as a type of clothing which use was determined by time and circumstances and as a phenomenon, which emerged in a small closed community of islands but soon became popular and widely used, thus taking on a nation-wide symbolic meaning that has persisted until the present day.

The study also points to the possible reciprocal influences

derived from the contacts of the inhabitants of the islands with the

population and folk art of other ethnic groups in the Baltic area, especially in

Scandinavia.

The first chapter describes the origin of knitting as a handicraft technique and its probable distribution routes to Estonia and the islands. Parallels are drawn with knitted sweaters of other countries of the Baltic area as a possible source for the emerging of the tradition on the Estonian islands.

The second chapter provides an overview of knitted sweaters of the Estonian islands preserved in museums, and of the written sources containing information about making and wearing them. On the islands regional characteristics developed, giving the sweaters a unique appearance.

The third chapter describes the used method, based on the holistic approach to culture, and applying it to the collected material. According to the holistic approach, information about the tradition (and the object) is obtained in the context necessary for its existence, and for understanding the tradition the system has to be considered in its entirety. An object is attributed different functions in the context and through that different meanings are assigned to it.

The knitted sweaters from the islands of Estonia, which came in use in the second half of the 19th century as a part of the national costume, served on the one hand as a transitional stage from the traditional home-made clothing to the manufactured, and on the other hand they became items of clothing, unique on each island, that were used even after the abandoning of national costume elsewhere in Estonia. In a way the sweaters became a source of information about the vitality of local clothing tradition. They represented the identity of a small group and for many became the symbol used to determine the boundary between `self' and `other'.

Jean-Loup Rousselot

For a long time the subsistence of Canadian Inuits, or Eskimos, depended on the cost of hunting products, of fur, in particular. The migratory lifestyle kept their households free of any excess objects, which is why their original artistic self-expression was limited to decorating objects of utility, including the series of pictures used at storytelling. After WWII the Canadian government launched a pilot project to support the population of Hudson Bay, in the course of which James A. Houston (born in 1921) was commissioned to create models of miniature plastic art, which could be used by the local population to produce miniature steatite figures. This form of Inuit folk art, which emerged only sixty years ago, has by now produced a number of artists with an interesting signature, like minimalist Lucy Tasseor from Keewatin, Joanassie (Joanassie Manning) from Cape Dorset and Peter Sevogat from Baker Lake. The artists have a high social position in their home communities.

Roger Pierre Turine

There are thousands of tribes in Africa, but not all of them have created statues or other objects of art that can be regarded as the creative masterpieces of their handicraftsmen. Eastern and Southern Africa are more passive in their creative expression than Western and Central Africa, which have given the majority of the rich and beautiful legacy of sculptural art. African idols have always been created only by settled tribes. Aesthetics never exists there without the force of the sacred. An African regards a work of art positively as long as it corresponds to the need of the person who ordered it and who wishes to contact the ancestors by means of a mediator. A sculptor - often also a village blacksmith - is, depending on the tradition and situation, hated, feared or admired among his close relatives.

In 2003 I introduced the art of the Baule and Lobi in my collection in Rakvere, Estonia. The aesthetics of the Baule was one of the first to capture the attention of the Western world already in the early 20th century, whereas the Lobi art was discovered only recently.

The Estonian National Museum holds valuable Mangbetu and Bembe objects, given to the museum by the Solomentsev brothers already before the World War II. These items have been collected in the areas of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Enn Kasak, Roomet Jakapi

The works of modern natural scientists and philosophers attributed great significance to the theme of human death and reincarnation. Concomitant to this was the discussion whether a reborn person is the same, or only resembles the one who died, i.e. the issue of numeric and qualitative identity. Discussions about the immortality of the soul, the possible existence and activity of the soul in and outside a physical body, the fate of soul after death, etc. were also considered of vital importance. The seventeenth-century English philosophy was based on the tenets of the Anglican Church about the absolute immortality of soul. John Locke, among other things, posed the question of the moral responsibility of the soul, especially from the aspect of postmortem destiny. The most common view of the time, however, was that the death of a human denies the possibility of repenting his sins: supernal bliss or torment in hell is the consequence of one's worldly actions.

Piret Õunapuu

Ceramics has never had particular significance in Estonian folk art. Traditionally, the Estonians expressed their creativity by cutting wood or forging iron. Thus, we cannot speak about popular tradition of folk ceramics, as it is a relatively recent field of art or consumer art.

Throughout times, Maanus Mikkel's creation has possessed the

underlying quality that enables to call it ethnic art, regardless of the

stylistic changes it has undergone. His works create the sense of a certain

paradigm.

A major part of Mikkel's creation, regardless of the technique, appears expressive, robust. Virility of his art is emphasised by the use of rough clay and often also irregular form. Although being primordially Ugric, the theme has not a single speck of grotesque in it. Figures are blown bigger, and have nothing in them indicative of the usual reticence of the Estonians. Most of the works are serious; others express a small hint of tongue-in-cheek irony.

It is not very common to ceramic pottery to have animate creatures depicted on them. Mikkel's creation almost always has clearly animate representations, though sometimes of unknown origin, including, for example, flying dragons as well as the tentative category of prehistoric animals. The figures, which sometimes disappear from the pottery only to re-emerge later, represent creatures of the times before the Ice Age. Of known species the most popular representations are that of bat and fish, even though some fish seem to favour flying, too. Some earlier works are reminiscent of prehistoric cave art, but this style has become considerably rarer.

The new figures that have appeared in his work are humans - men and women. Love in the inane. Mikkel's earlier darker tone has become considerably brighter, his lines more round and fluent. Fortunately, the primordial fossils have not altogether disappeared in Mikkel's work; thus his already versatile world has acquired a new dimension. And who knows what course his art will take in the future.

Jüri Arrak

Considerations of a famous Estonian artist on the evolvement and views on his creation. The artist introduces his sources of inspiration and describes his journey to religious art.

Jüri Arrak

The famous Estonian artist's considerations on the relationship of an artist and religion and his interpretation of the system of angels.

News, overviews

Ello Säärits 13.10.1914-19.07.2005

On the 19th of July, a meritous folklore collector and literary scientist

Ello Kirss-Säärits died at age 90.

Introduction of textile artist Riina Tomberg's MA thesis

Vatid, troid, vamsad. Silmkoelised kampsunid Eesti

saartel ('Knitted Sweaters on Estonian Islands', Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia 2005. Supervisors

Annemor Sundbø and Virve Tuubel) by Mare Kõiva.

Introduction of textile artist Christi Kütt's MA thesis

Lääne-Eesti pulmavaibad - etnograafiline aines, pedagoogiline ja loominguline aspekt

('Western Estonian Wedding Blankets - Ethnographic Source, Pedagogical and

Creative Aspects', Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia 2005. Supervisors Anu

Raud and Ene Kõresaar) by Piret Õunapuu.

Max Planck Institute in Halle

Introduction of the conference on legal anthropology

Order and Disorder, held in November 26-27, 2004 at the Max Planck Institute for

Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany, by Aimar Ventsel.

Introduction of the first interdisciplinary academic conference on sacred groves Ajaloolised looduslikud pühapaigad eile, täna, homme, held on March 17, 2005 (and organised by Maavalla Koda, The National Heritage Board, Estonian Literary Museum, Estonian Folklore Archives and the Department of History at the University of Tartu) by Marju Torp-Kõivupuu.

The seminar on the Erzyan language held on April 16, 2005, was

dedicated to the anniversary of Erzyan language reformer Anatoli Ryabov

(1894-1938). An overview of seminar discussions by Kristi Salve.

|

Spring Storms and Seminar of the Department of Folkloristics on May 24-25, 2005

Members of the Department of Folkloristics argue on the topics discussed on May seminars. Thunder storm on the evening of May 24 formed a natural context for the seminar held at Mesilinnu Saloon in Nõuni. Regardless of the thundering and flashes of lightning outside, the discussions remained effective and matter-of-fact. Overview by Mare Kalda. |

|

In July 2004 a group of ten students of the Estonian Academy of

Arts conducted fieldwork in the Setu County on the territory of Estonia and

the Russian Federation with an aim to find and record ethnographical

material interesting from the viewpoint of folk art. Overview of the

expedition by Kadri Viires.

on Folk Art

During October 10 - November 9, 2003 the international exhibition

of outsider art and art brut was displayed at the Tallinn Art Hall, and

on October 17-18, 2003 the international conference and the film

programme Insulting the Jellyfish was held.

The gallery of Estonian folk artists is available on the Internet at http://www.metsas.ee/et/galeriimetsikud. METSIKUD (`The Wild Ones'), the online gallery of contemporary folk art and art brut joined the portal metsas.ee in September 2004. The gallery is managed by Sigrid Saarep.

In Kiasma Museum of Modern Art in Helsinki the exhibition of non-academic or outsider art (art brut, eccentrics, visionaries) In Another World was opened on May 14, 2005. The opening of the exhibition coincided with an international conference on May 24-26 with presentations by the leading experts on outsider art.

Overview of the art events by Sigrid Saarep.

From September 9, 2004 to the end of the year, African art was

displayed in the exhibition hall of the Estonian National Museum. The purpose

of the exhibition Traditional Creativity in

Africa was to display the small (about 150 objects) but interesting collection of African artwork held

at the Estonian National Museum. Curator of the exhibition was

Laur Vallikivi, display was arranged by Krista Roosi. This was the second

exhibition in Estonia to introduce African art and culture after the

exhibition Beauty and Power held a year earlier at the City Gallery of Rakvere.

Introduction of the exhibition by Kadri Viires.

an Example of a Lifestyle

Introduction of Kaljo Põllu's book on traditional architecture on the

island of Hiiumaa based on the material of fieldwork expeditions of the

Estonian Academy of Art Hiiumaa rahvapärane ehituskunst: Eesti

Kunstiakadeemia uurimisreiside materjalide

põhjal (Tartu: Ilmamaa 2004. 366, [1] p.)

by ethnologist and artist Lembit Karu.

Introduction of Rolf Wilhelm Brednich's book

www.worldwidewitz.com: Humor in Cyberspace (Herder Spektrum 5547. Freiburg & Basel &

Wien: Herder 2005, 160 pp.) by Sabine Wienker-Piepho.

The study "Russkij Berlin: Migranten und Medien in Berlin und London" (Russian Berlin: migrants and media in Berlin and London) by Tsypylma Darieva published by German publishing house Mystery in the series Zeithorisonte (9/2004) will be introduced by Aimar Ventsel.