Mäetagused vol. 65

Summary

-

How to specify borders in cultural and research landscapes?

How to specify borders in cultural and research landscapes?

Tiiu Jaago

Keywords: border, interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity

Introduction into the special issue dedicated to borders and border areas. As the authors analyse social and cultural environments that are not in contact in time or space, the articles represent rather different viewpoints and ways of raising questions. Such a range of articles, however, enables dwelling on two topics: symbolic borders in society and interdisciplinarity as a border area between different domains.

-

-

Towards the border lore and border folk: Folklore research on the interdisciplinary research field

Tuulikki Kurki

Keywords: border studies, culture, folklore research, multi- and interdisciplinary research, people, tradition

The article studies folklore research in the context of the multidisciplinary research field of border studies. The article is a conceptual thought experiment enquiring how the central concepts of folklore, such as ‘people’, ‘tradition’, and ‘identity’ can be redefined when they are examined together with the central concepts of border studies, such as ‘border’ and ‘borderland’. The latter function as a means to reflexively study and deconstruct the concepts ‘people’, ‘tradition’, and ‘identity’. The article claims that in the context of national order (Foucault) the borderland cultures and identities appear as the ‘other’ and as incompatible elements of national cultures and identities. Therefore, until recently, the borderland cultures and identities have not been recognised as objects of research in the history of folklore research. In the context of multidisciplinary border studies the border cultures, identities, and traditions may appear as negotiable, dynamic, and genuine forms. It is important for folklore research to recognise these forms as the objects of research. When these forms are recognised in folklore research, it is possible to renew concepts and methods in research so that they become deterritorially defined, transnational, and post-national. The examined material includes articles in folklore research and border studies.

-

-

Possibilities for using folklore in studying peasant history

Possibilities for using folklore in studying peasant history

Ülle Tarkiainen

Keywords: agrarian history, microhistory, narrating the past, oral history, settlement history

The possibilities for using folklore in studying history are directly dependent on the raised problem. In memories about the distant past, reality and fiction are often mixed up, which is why historians may regard the reliability of such stories as low. Still, such folklore shows what was valued, which events were felt to be significant and important. For historians, problems have been posed by the reliability and difficulties in dating the lore. In connection with the emergence of microhistory, more and more attention is being paid to how and what people thought, and it is often very difficult to find answers to this question in written sources.

This article observes the possibilities for using historical tradition in the studies of agrarian and settlement history and, more specifically, five narrow topics that concern border markers, the emergence of villages, land use in farms, inheritance matters, and beggars. Oral tradition about the founding of villages and farms and their first settlers is in most cases connected with the periods of war and the plague, immigration of people, or some other extraordinary event. Descriptions of everyday life, which are abundantly found in folk memory, usually speak about well known and familiar things. At the same time, they considerably help to broaden notions of the past and enable to find out the peasants’ attitudes towards and evaluations of one or another event or phenomenon. As a result of taking folklore into consideration, the picture of history becomes much more differentiated and colourful.

The folklore that has been observed in this article is closely connected with the village society, and it primarily reveals notions connected with the farm people’s everyday life. Archive sources usually disclose them from quite a different point of view. As a result of the analysis, we have reached the conclusion that the best results are achieved when historical tradition is taken into account for relatively recent events, those that have happened since the second half of the 19th century, and under circumstances in which spatial relationships have not considerably changed. The use of earlier lore is more complicated, although it also enables us to see people’s attitudes, which gives a ‘soul’ to the discussed phenomena. The biggest difference is that archive materials, naturally, do not reflect the reasons hidden in the peasants’ mental world. Namely, this is why the use of folklore enables to provide important extra material for studying settlement and agrarian history, which supplements a rational picture about past events and processes, and enables to open up deeper backgrounds to what happened.

-

-

Collecting, studying, and teaching Deaf folklore

Collecting, studying, and teaching Deaf folklore

Liina Paales

Keywords: Deafhood, Deaf folklore, Estonian Deaf community, Estonian Sign Language, Facebook, folklore

Different aspects of deafness are dealt with within the realms of, for example, medicine, law, educational science, and psychology. This article focuses on the Deaf folk group, and more specifically on the Estonian Deaf community and its culture from the viewpoint of folkloristics. The article views the possibilities of folklore research in studying deafness and Deafhood and in the application of such information.

This article springs from the approach of the American folklorist Alan Dundes on folk groups. The term ’folk group’ enables to be unspecific about whether the group is a minority, ethnos, disability, or any other type of group. For Deaf group identity, different manifestations of similarity are considered, like, for example, Deafhood, sign language skills, and knowledge of Deaf culture.

In Estonia the number of Deaf community members is approximately 1300. The Estonian Sign Language is estimated to have about 4500 regular deaf and hearing users. In Estonia, 1–2 deaf babies are born for every 1000 children, approximately 15 children per year. Most of the deaf children are born into hearing families; they are switched into the cyborgization process and go to regular schools. From the cultural point of view, such deaf children grow into hearing people.

The Estonian Sign Language started to be taught at the University of Tartu in the 1990s. The author, who is a hearing person, started collecting and studying Estonian Deaf folklore in the middle of the 1990s. The subject course in Deaf folklore was first taught at the University of Tartu in the 2007/2008 academic year under the curriculum Estonian Sign Language interpreter. In order to describe Deaf folklore, it was necessary to create terminology in Estonian and in the Estonian Sign Language. For the purpose of the Deaf folklore course, video files and folklore texts of folklore terms in the Estonian Sign Language were recorded in cooperation with Deaf people.

A new environment for collecting Estonian Deaf folklore is the Facebook group Eesti kurtide folkloor (Estonian Deaf folklore), which can be joined by sending a request. This group was formed by Deaf interpreter Gretel Murd on 5/03/2015. The group has more than 500 deaf and hearing members and three administrators (two deaf and one hearing). Its members have posted videos, shared photos and written texts in Estonian. Video texts contain, for example, jokes, sign play, riddles, memories from the school for the Deaf, and experience stories.

-

-

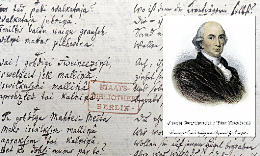

Latvian folk songs in Johann Gottfried Herder’s manuscripts collection

Latvian folk songs in Johann Gottfried Herder’s manuscripts collection

Beata Paškevica

Keywords: Heinrich Baumann, Gustav Bergmann, Enlightenment, Jakob Benjamin Fischer, folk song, Johann Gottfried Herder, August Wilhelm Hupel, Latvian folk songs, Volkslieder / Stimmen der Völker in Liedern

The handwritten Latvian folk songs in Johann Gottfried Herder’s manuscripts collection at the Prussian Cultural Heritage Manuscript Department of the Berlin State Library (also known as “Livonian collection”, as titled by Leonid Arbusow) are a testimony of the folk songs collection campaign at Herder’s request in 1777 and 1778.

The authors who responded to Herder’s request and collected, commented, and translated Latvian folk songs have been identified in some cases, but there are also manuscripts of unidentified authorship; the identity of their authors has been widely discussed in previous studies. In the present study, handwritings in documents held at the National Library of Latvia, the Academic Library of the University of Latvia, the National Archive of Latvia, and the Historical Archive of Latvia have been compared and all collectors of Latvian folk songs in Herder’s personal archives have been identified. It has been found that the unidentified handwritings belong to Heinrich Baumann, Gustav Bergmann, Jakob Benjamin Fischer, and August Wilhelm Hupel. It has been discovered that manuscripts No. 50 and No. 53.1 of Herder’s personal archives were written by Gustav Bergmann; manuscript No. 51 was written by Jakob Benjamin Fischer (it includes texts from the 50th manuscript by Baumann and the 52nd manuscript by Bergmann as well as some original texts which were missing in both Baumann’s and Bergmann’s manuscripts); manuscript No. 52 was written by Gustav Bergmann, and manuscript No. 53.2 was written by August Wilhelm Hupel.

Herder selected parts of manuscripts No. 50, 51, and 52 to publish them in a separate section titled “Fragments of Latvian Songs” (Fragmente lettischer Lieder) in his collection “Folk Songs” (1778/1779). Encompassing six texts, “Fragments of Latvian Songs” is the first set of Latvian folk songs in Herder’s volume. There is also a second collection, titled “The Song of the Spring” (Frühlingslied) in which five texts are included. The original handwritten texts of “The Song of the Spring” have not been found in Herder’s personal archives in the Berlin State Library; therefore it must be assumed that Herder received yet another handwritten collection of folk songs which has been lost. For this reason, the number of songs in the lost collection remains unknown as well. Considering that “Fragments of Latvian Songs” were selected from eighty submitted texts (which included different variations of the same song), we can assume that “The Song of the Spring” has been similarly selected from a wider amount of texts according to rigid principles known only to Herder himself. Thanks to the cooperation of Livonian authors, Herder had a broad collection of Latvian folk songs in his possession.

-

-

Journeys and borders: Life stories from the aspect of border poetics

Tiiu Jaago

Keywords: border poetics, life story, real life-based story, war refugees

This article analyses descriptions of journeys and the emergence of territorial and symbolic borders in autobiographical texts. Historically, the descriptions are related to migration caused by World War II and, to a lesser extent (or in connection with the war), the establishment of Soviet power in Estonia.

The analysed life stories were narrated in the period from 1995 to 2011, and are stored in the “Estonian Life Stories” collection (EKLA f 350). The narrators were born in the late 1920s or early 1930s; at the time of the narrated events they were children, whose migration was not so much dependent on the historical situation, but the life, choices, and decisions of their parents and relatives. The theoretical starting point for analysing the texts is border poetics: How is the border depicted in narratives? How are different borders (territorial, state, cultural borders, the front line, symbolic borders in narrator’s changed status and self-image) intertwined in the narrative?

The narrators describe their journeys from Estonia to Germany, Finland, or Sweden, but no state borders are specified in the stories. Border crossing is revealed through signs, which could be generally described as safe and dangerous areas. The riskier or the more conflicting to the usual situation the experience was, the more detailed is its description. However, the narrator describes a process, which is why the conflict (and the focus of the description) does not have to be concentrated in just the one moment of crossing the border.

References to the border may emerge as indirect signs, for example, visually. German towns are described as being either in ruins or intact from the battles; descriptions of Stockholm point out its lit windows in contrast to the darkened windows of the wartime Estonia. Border-related signs are also disclosed in people’s behaviour or attitudes. For example, the problems of the inhabitants of Sweden, which was untouched by the war, seemed trivial to those escaping from the war. Symbolic borders also emerge in the changed status of the narrator as the main character of the story; for instance, upon arrival in another country an active person turns passive, into an observer and an object of other people’s actions, and then changes again into an active one, who makes decisions on shaping his or her fate in the new country of residence.

The border-poetic approach enables to view the narratives of people who escaped to the West during World War II not so much from the historical or memory-theoretical aspect as from the aspect of narration of borders. This makes it possible to place the topic of the 1944 flight into a more general panorama of escaping and crossing the border.

-

-

Mitra in India and Mithra in Iranian religions: A study on comparative mythology

Jaan Lahe, Martti Kalda

Keywords: Avesta, India, Iran, Mithra, Mitra, mythology, Sanskrit, Vedic literature

This article is a systematic approach to the character of deity, who bears the name Mitra in India, but in Iran is called Mithra (later Mihr). The study aims to give answers to three questions: 1) What are the similarities between the Indian Mitra and the Iranian Mithra, if we leave aside the name of the deity? 2) What are the differences between these two deities? 3) What are the changes that the depiction of Mitra/Mithra has gone through in Indian and Iranian mythologies? To answer these questions, the article first gives an overview of Mitra in India, then of Mithra in Iran, and finally compares the two.

Both approaches start with a comprehensive overview of sources. In India the main source for the study of Mitra is Vedic literature (ca 1500/1200–600/500 BC), namely the Rigveda, Atharvaveda, Yajurveda, and Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa. These sources are consistent, describing Mitra as a deity connected with the Sun, the incarnation of divine order, harmony, and friendship among mankind. Some light is thrown also on Mitra in post-Vedic literature, mainly in epic literature (ca 300/200 BC–200/300 AD).

In Iran, the sources are even more varied. They start with Iranian scripture Avesta (ca 1000–300 BC) and epigraphic sources from Achaemenian dynasty (6th–4th century BC), and continue with written sources from Greek and Roman writers (6th century BC to 3rd century AD), epigraphic material, and data from coins from Kushan (1st –3rd centuries AD) and Sassanid periods (3rd–7th centuries AD), not to forget Pahlavi writings from medieval Persia (7th–10th centuries AD). According to the sources, Iranian Mithra is a divine warrior, ruler of the worlds, judge of the dead, and protector against demons. He is still connected with the Sun, and helps the mankind, but more aggressively than Indian Mitra, who has ceded all his warlike attributes to his dual companion Varuṇa.

The article concludes that the cult of Mithra that was so influential in the Mediterranean region has probably borrowed more from Iran than India.

-

News, overviews

-

In memoriam

Erna Tampere

November 20, 1919 – September 3, 2016.

-

-

Birthday Greetings!

Rutt Hinrikus (70), Paul Hagu (70), Juri Berezkin (70), Mikk Sarv (65), Monika Kropej (60), Urmas Sutrop (60), Aado Lintrop (60), Diane Goldstein (60), Tatiana Minniyakhmetova (55), Virve Sarapik (55), Kadri Tamm (55), Kristi Metste (55), Ell Vahtramäe (50), Risto Järv (45), Piret Voolaid (45), Raivo Kalle (40), Nikolay Kuznetsov (40), Katre Kikas (35).

-

-

Doctoral dissertation emitting good energy

On June 10, 2016, Kristel Kirvari defended her doctoral dissertation titled “Dowsing as a link between natural and supernatural: Folkloristic reflections on water veins, Earth radiation and dowsing practice” at the University of Tartu. An overview by Mare Kalda is available in English in Vol. 66 of Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, at http//www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol66/n02.pdf.

-

-

Thirty-three presentations on contemporary legends

The 34th conference of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research was held in Tallinn from June 28 to July 2, 2016. An overview by Mare Kalda is available in English in Vol. 66 of Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, at http//www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol66/n03.pdf.

-

-

Ethnobotanist Renata Sõukand is the first Estonian scholar in the field of humanities to win the most prestigious grant in Europe

In September, the European Research Council announced the Starting Grant holders for 2016. The most prestigious European Starting Grant of nearly 1.5 million euro was given to Renata Sõukand, ethnobotanist of the Estonian Literary Museum.

-

-

The Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies led by the Estonian Literary Museum started work

In February 2016, nine centres of excellence were established in Estonia. In the field of humanities, the Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies (CEES), administered by the Estonian Literary Museum, won the grant of the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union for 2016–2023. The centre is led by Mare Kõiva, leading researcher of the Department of Folkloristics at the Literary Museum, and it brings together fifteen personal and institutional research groups.

An overview is given by Piret Voolaid.

-

-

Calendar

A brief summary of the events of Estonian folklorists from July to December 2016.

-

-

New research archive at the Estonian Literary Museum.

The new archive is introduced by Mare Kõiva.

-