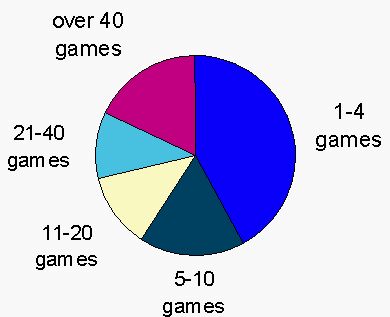

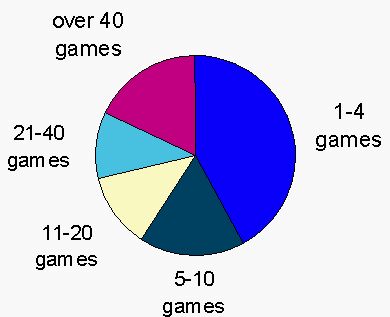

Diagram 1. Schools as contributors of games.

Our 1992 appeal to collect children's lore has enriched the Estonian Folklore Archives with a considerable number of game descriptions noted down by the players. To a folklorist the material looks inviting from several aspects. One could, for example, analyse what games are preferred by different sex or age groups, or find their places on popularity axis, or concentrate on the most frequent practical jokes admitted by their authors. Also, one could focus on children's attitudes towards games and playing. I, however, decided to consider the material from the point of view of the traditional and the more recent traits of the games described.

In order to help the prospective participants of the competition, schools were provided with a nine-point questionnaire of which games constituted the last point. Yet relevant material could be found under other subdivisions as well. If one takes an enlarged view of the notion of game, most of the material accumulated as a result of this competition could probably be encompassed, as there is hardly an activity described there that misses an element of game.

Comparing the game descriptions received with written records of other folklore genres, there appears a difficulty in putting down game descriptions. In the case of games a child will find itself confronted by quite a different task: he knows what needs to be done in order to play the game, but now it has to be described in so many words. The younger the child, the less he is able to reach the level of abstraction necessary for covering all of the relevant details. I like Elastic Skipping. There you can jump. For 6th and 7th-formers this has ceased to be a problem. The best criterion to evaluate a description is probably whether it is clear enough to permit one start playing the game, or, if not, how many additional questions are needed to ask. Full descriptions (with figures and schemes, if necessary) could rather be expected from those aged sixteen to eighteen, but they have already lost their former lust for playing games.

The material received contained, though, quite a number of good descriptions, characterized by a fluent, yet concise wording, clear coloured schemes and illustrations.

Games and Written Sources. Copying

In copying there are two main patterns observed. One is cribbing from ones deskmate, classmates or siblings. Beside direct copying the child may just have asked, "What games did you put down?", the result being, of course, that the selection becomes biased. Such material makes it quite easy to guess who is whose deskmate or bosom friend. Similar material is also selected by children of one and the same family, but surely even there many games were just forgotten to be mentioned. Such occcasional preference of this or that game does not prove their being actually unpopular. A scanty harvest of descriptions need not always be a sign of low popularity.

The other strategy makes statistics even less reliable. Some pupils, probably underestimating the games they play, or their own power of written expression, took the trouble to look round for books in the field. Luckily, there are not many of such available. Eesti rahvamänge (Estonian folk games) by Alekasander Kalamees (1973)2 is too old to be found in many homes nowadays. In any case its influence has been negligible.

A little more often one may find evidence to the use of 1000 mängu (1000 games to be played in gym-hall, playground, field, town, country, or room) by the Chekh author Milo Zapletal (1985). There are some word-for-word copyings, but also overt references to the book as a possible source of new games to play.

Another popular source seems to have been the book called Ühise pere lapsed (Children of one family), where every republic of the former Soviet Union is represented on two pages containing a doll, its costume, a bookmark with a typical ornament, and the description of a game. To prove the folk origin of every game is beyond our competence, but Estonia, at least, is represented by a game called Birds that was first described in 1892. In addition, games have been described in children's magazines. Each 1991 issue of Põhjanael, for example, brings a game of an exotic nation on its back cover. But those have not influenced our material. In general the material is rather reliable and authentic.

Collectors. Schools and Individual Competitors

The volumes of school tradition received in answer to our appeal include about 3,500 games, 500 pranks and 780 counting-out rhymes, plus aconsiderable number of calculating and match rearrangement tasks.

Games were noted down by 630 students from 89 schools, which makes up 34.5% of all participants of the school traditions collecting campaign. The percentage of girls (70%) was higher among the contributors of games than among those who had confined their efforts to the rest of the themes proposed (62%). The reason, however, is not the girls' greater lust for playing games, but rather their more conscientious attitude to the filling in of the lengthy questionnaire. In some kinds of games (exertion, cards, monetary games etc.) the boys' competence most likely surpasses that of the girls.

School contributions differed in volume, detail and contents. By the number of games contributed schools can be divided into five groups:

Age of Contributors

Games had been written down by students from forms 2-12. The youngest participants were all individual contenders. As appears from Diagram 2 most of the games were sent in by 5th-10th-formers. The most active in this respect were the 8th-formers, the runners-up being Forms 5 and 10. Forms 3, 4 and 12 were poorly represented. The school-leavers (9th and 12th forms) as a rule avoid the work, with a few especially enthusiastic exceptions. There is much in common between the age-structures of the contributors of games and those of counting-out rhymes.

The practically coincident beginning and end of the two graphs on Diagram 2 are evidently the result of the age limits of the participants as well as of the staying aside of the first-formers and the school-leavers of both basic and secondary school. The differences can be accounted for by the specific traits of the two kinds of material and the different attitudes assumed towards them by different age groups. A fifth-former will find it much easier to put down a counting-out rhyme or a game-starting formula than to describe a game. Forms 6-7 stand out for the pupils' wish to look more adult in every respect and their studious effort to avoid looking childish in any way. This may well be the reason underlying the sharp drop in the counting-out rhymes sent in by this age-group.

There were also remarkable differences between the styles of writing used in different classes. Whether games were described or just listed seems to have depended on the teacher or on the class leader.

The largest number of games and pranks had been described by Jaagup Kippar, a tenth-former from Tallinn. His contribution could almost be classified as memoirs. The best part were the games and pranks of which there were 83. They all belong to the repertoire of a small circle consisting of the collector and his classmates. The work stands out especially for a clearly expressed attitude, an evaluative and context-sensitive approach. Every game description is supplied by comments on how the game was learnt, what was the company's first opinion of the game, how it was liked (or disliked) by teachers or other adults, when and in whose company it was usually played, and when one got tired of it. There are also many photos (of class parties) from the author's private collection to illustrate the text.

Game presentation was also excellent in Maarja Villandi's collection (from Tartu) that looks like a serious study report. There were 49 games described, while the descriptions were thorough indeed including the informant's names, information about when and where and by whom the game was played. There were not only games that she had played herself, but also those remembered by her mother, father and brother.

Besides the two collectors just mentioned there were quite a number of other diligent and thoroughgoing contributors.

Classification of Games

Any analysis of any substantial number of games would hardly be conceivable without a preliminary classification. The problem is what should be taken for the basic criterion - some common features of the games, players, time and place of playing? Each approach has its advantages enabling one to view the material from a different angle. Proceeding from the sex of the players one will obtain a four-way classification: 1) boys' games (games of motion, ball games, card games); 2) girl's games (Hopscotch and skipping, Granny's Ball of Yarn, Elastic Skipping); 3) mixed games (many social games like Long Nose, Eye-Winking, Kiss-Kiss, etc.; 4) sex-neutral games (Hide-and-Seek, Tag).

Such classification is not very strict. It would be more correct to say that boys, for example, prefer rough-and-tumble sports games whereas the girls like those games that serve to set off and cultivate deftness, lightness and grace of movement. How the player's sex may influence their choice of games has been considered in great detail by the Finnish folklorist Leea Virtanen. According to her, modern girls have expanded their games sphere to the formerly exclusively boy's games, thus acquiring more and more of manly qualities (Virtanen 1984:27).

A still more differentiated picture will emerge if we proceed from the age of the players: junior (primary school) games, teenager games, senior (secondary school) games. Younger schoolchildren seem to prefer all kinds of chasing games (Tag) as well as skipping, Hopscotch and various imaginative games. In the teens the focus shifts to games requiring more stamina and skilful action. The girls are fond of Elastic Skipping, the boys prefer various ball games and also other games that serve to train accuracy. In senior forms sports games usually give way to social games (with boys that usually happens considerably later than with girls).

According to the playgrounds indoor and outdoor games can be differentiated.

Indoor games can be played at home, or at school (in the classroom, corridor, cloakroom, gym-hall). Outdoor games are played near home, or schoolhouse, in the street, in woods, etc. As a rule, outdoor games require more space and may, to an extent, depend on weather. As our survey was done in spring, winter games were mostly forgotten to mention. There were but a few children who pointed out Snowballs or Ice-Hockey. The ruling opinion was that summer is the best playing season as the days are warm and void of school obligations.

Another difference that looked relevant to the children was whether the games were played at school or at home. School games (ball games, social games) tend to require more participants. In home-played games the players are not so numerous, while the environment seems to favour various types of hide-and-seek and imaginative games. Writing games are played both at home and at a dull lesson. Breaks are suitable for running, girls' Hopscotch, and boys' football (that can also be played with an old beverage can, for example). A sports lesson will naturally include some sports games, at class parties one cannot do without social games. As games played at home during birthday parties must usually fit into a rather confined space, various writing games are played there, including quizzes of an intimate kind.

Still another possibility is to classify games according to their number of participants. One can play some games alone. These include simpler imaginative games such as At Home (together with dolls), At School, At Shopping, At Doctor's etc. In one's own company it is also possible to train certain skills needed in playing sports games (Hopscotch, Ball-Catching School, Rope-Skipping etc.). Even Elastic Skipping with its almost acrobatic elements can, in principle, be practised at home alone, while the bands are fixed to chairs and stools. Only the excitement of competition is missing. Two children have much more to choose from - but not various tests of skills, including sharpshooting. There are also many writing games that can be played by two, such as Hangman, or Noughts and Crosses (Seabattle). Two children could also manage to play Elastic Skipping, although a bigger company suits the games better. Most board games also require a minimum of two players. Some games are played in pairs (e.g. Twist may be played by two pairs of children). Three is the minimum of elastic skippers as well as of players of certain ball games (Dog et al.). Four players are necessary to start Four to Panes (also called Vibra). Some children have pointed out that at least four are suitable company for quite a number of games. In games for more than four children, the actual number of players is mostly irrelevant. Running and chasing games, Hide-and-Seek, social games are all the more exciting the bigger the company. Some games, though, need an odd number of players (Odd-Man-Out, Eye-Winking) whereas some others require an even number of participants (Long Nose, team games), yet in most cases the number may vary freely (The Old Pants of My Grandfather, Bottle Spinning, Blindman's Buff, Tag etc.).

The most important classification should, however, be based on the essence of games. Yet it is not so easy to find a universal criterion for classifying the whole gamut of games. Previous experience shows that more often than not the researcher's aim has been just to describe the most popular games rather than to develop an impeccable classification. As to our material, it also seems quite resistant to attempts of conforming it to a universal system avoiding both omissions and double inclusions.

The available classifications of Estonian folk games are few. The earliest attempts were documented by Anna Raudkats and Aleksander Kalamees, who both worked as teachers of physical training. The very first classification was attempted by Anna Raudkats in the first fascicle of her series Mängud (Games) (1924). Her division of the games into kinetic games3, singing games and social games was implemented in her book Tütarlaste mängud (Girls' games) (Raudkats 1933:9) which was written from the point of view of a gymnast and dancing teacher, and was meant for use by girls' organizations, at school and at home. In her book Mängud IV the notion of social games has been expanded so that beside the indoor kinetic games suitable for playing in a confined space one can also find some outdoor kinetic games including various races, ball games, etc. (Raudkats 1927.)

A. Kalamees has approached the material from different angles. According to the basic action or the instruments used, he differentiates between 1) social games, 2) pawn redemption games, 3) games using objects made of wood or other materials, 4) paper games, 5) stone and pebble games, 6) chasing and catching games, 7) games to demonstrate strength and skill, 8) ball games, 9) hitting and throwing games (Kalamees 1936).4

The folklorist Richard Viidalepp in his instructions as to how folk games should be collected (1934) considers folk games as a natural part of folklore. He classifies the games into 1) singing games, 2) winter games, 3) Christmas games, 4) games played at spring holidays and festivals, 5) various sitting and outdoor games, 6) moving games, 7) hitting and throwing games, 8) ball games, 9) contests and other sports games, 10) pawn redemption games, 11) card games, 12) games played by little children, 13) other games. Here, too, the criteria underlying the classification are several (action, time, player, object).

Viidalepp's instructions were addressed to schoolchildren. The material thereby collected was arranged into a Games File at the Estonian Folklore Archives. In principle the structure of the file follows the above scheme being, however, more concrete and more systematic. More emphasis has been laid on the association of some games with calendar and family traditions (festival games, wedding games). The games formerly called sitting and outdoor games have been joined under the common heading of social games. Several additional subclasses absent in the instructions, yet abundantly represented in the collected material (stone and pebble games, writing games, Hopscotch, hiding games, blindman's games etc.) have been pointed out.

The current classification divides the material first into 1) kinetic games, 2) social games and 3) pretending games. Kinetic games are in turn divided into running games, jumping and skipping games, skill-demonstrating games, strength-demonstrating games and throwing games. This division differs from that of Viidalepp who interprets kinetic games as running games only (1934:20). The current classification is closer to those preferred by gymnasts (Isop 1974:9; 356-359).

On the other hand, Peter and Iona Opie classify the games played by the English children as follows: chasing games, catching games, seeking games, hunting games, racing games, duelling games, exerting games, daring games, guessing games, acting games, pretending games (1984:XXVI-XXVII).

In the near future the classification of games remains an issue of discussion. Whether the classification should rest on the main activity the game is based on, or on its main motif (Opie 1984:VI), or on its end (Ribenis 1995:38), or on some other criterion depends on the purpose of the study in question. Every fresh approach will shed some light on a different aspect of the game as a phenomenon with a complex structure.

In the rest of the article, two subgenres of kinetic games, running and jumping games are discussed in detail.

Kinetic Games

Kinetic games serve to demonstrate and stimulate the development of physical abilities (speed, skill, accuracy, strength) by comparing the performances of players. To a greater or lesser extent those games are all based on competition, e.g. in Tag the one caught will become the new chaser and the game usually consists of many such short cycles. But there are also variants in which there is but one long cycle of leaving out the slowest and clumsiest players one by one until the winner is found out (Hopa-hopa et al.). Moving games require a lot of energy and develop stamina. The games are most popular among the primary and medium level schoolchildren. In the 7th or 8th form, children usually discover that they have outgrown those games. As a rule, sports games require more space and players than some other games. They are the best to play outdoors, but school corridors and gym-halls fit the purpose as well.

According to the basic activity the games can be divided into: 1) running games, 2) jumping games, 3) skill-demonstrating games, 4) strength-demonstrating games 5) throwing games.

I. Running Games

Running games are usually played most enthusiastically by pre-school and primary school children. At this age it is difficult to stay long in any fixed position. This group has also been called chasing and catching games. Running games belong to the ancient layer of games, which in earlier times have quite obviously been practised by adults as well. It would be naive to look for the original home of those games with any particular people. They are known all over the world, while the underlying pattern of behaviour is archaic, primeval and stable. Basically they are imitations of hunting. This may even be reflected in the name of the game (kull `hawk' = Tag).

The chasing games5 form a vast group with numerous subgroupings. But they all involve two parties - the chasers and the fugitives, and there are two possible situations: (A) one player chases all the rest, or (B) one group is chasing another group. In the text to follow, separate mention will also be made of games with increasing and decreasing groups (C), and some other possibilities (D).

A. One Player Chases All the Rest

The principal game of group A is Tag.6 It would be hard indeed to find a school where the game was not mentioned, or moreover, a child who has never heard of the game. In children's own opinion, it is also their most popular game. What was surprising was the great variety of variants and names currently used.

Name. One and the same name usually applies to both the game and the chaser, but sometimes there is also a difference. The whole material contained a large variety of names, including those used throughout a wider area (kull, kula, mats, läts, lets, leka) and those of a more restricted local distribution (hoop, kirp, käpp, laapa, pedi, perä). The most widespread name was kull.

As a result of comparing those names with the game files available at the Estonian Folklore Archives it turned out that a considerable part of the list above represent a fairly old local tradition (see Map 1). In the old tradition, the most widely used names were kull and läts, the former of which would characterize the slightly preponderant eastern half of Estonia, whereas the latter would rather be used in the western part. But kull is met also in the Archives under many old names such as Crazy Dog (hullukoera mäng); Goshawk (kanakull), etc. Some names (The Tilling of Hawk's Land (kullimaa tegemine); The Picking of Hawk's Oats (kulli kaera katkumine); Hawks and Hen (kullid ja kanad) etc.) suggest a connection with old singing games. The variants, however, were fewer than can be found in modern material. According to the Archives the most popular Tag games played in the old were Stone, Wood, Squatting, Stump and Hummock Tags.

The names bear traces of influences received from the neighbouring peoples. The northern Estonian laapa (as well as its name translated into Estonian käpp `paw') is an obvious loan from the Russian liapki, lepki (Russian lapa `paw'). Of the Russian names for the game (salki, piatnishki, lovitki, lovushki, etc. (Byleyeva-Grigoryev 1985:15)), the most popular is the first one, that also means `hawk'. There is even a corresponding verb salit' `to touch somebody thus making him or her a new tag', that has no one-word equivalent in Estonian in which language the corresponding idea is expressed by a phrase kulliks lööma.

From the lexical point of view the name may denote either the chaser or the act of touching or catching the fugitive. In the former case the name may reveal one of the following two attitudes: the chaser is a frightening figure (hawk) or the chaser is not really dangerous at all, the name intimating a humorous, teasing attitude (kirp `flea', perä `the last, bottom'). The ways of touching the fugitive are represented by a motley succession of synonyms like hoop, läts, lets, mats, pats `punch, slap'. It is notable that the name kull is found also in Sweden near Stockholm (Tillhagen, Dencker 1949:187). The original meaning of this word has been `light touch' (SOAB, vol 15:3138/9).7 Various other tag game names occurring in different regions of Sweden can also be translated as `to touch' (derivative from Icelandic daltar, Swedish-Danish pjåttar, even Danish (slå) basken `to hit hard'). Here one could probably also include käpp and laapa denoting the hitting hand.

Kull has yielded several derivatives such as kula, kulu and kuluk. Various names with the kula-component (Stone Tag (kivikula), Squatting Tag (kükakula)) have been recorded as early as the late 1920s and 1930s. The kulu and kuluk forms are derivatives from the kull-kula-kulu line, the u-suffix has lent the stem a substantival meaning, the k-suffix is often used in slang. Although the name draakula also seems to contain a kula component, it must have been motivated by the nightmarish hero of the famous horror film.8

Participants. Tag is played by boys as well as by girls. The number of players is not fixed. As a rule the number is between three and ten. A bigger company is believed to render the game less exciting, unless there is more than one tag. The game is played by children under 12 usually. Later it is played more and more seldom or replaced by some more comfortable variants (Window-Sill Tag, Duster Tag) that require less running.

Playing grounds. Tag is site-neutral in the sense of being played indoors as well as outdoors, on a limited as well as on an undefined territory. In the former case the game is more exciting as a compact area will shorten the chasing time and so everybody must be on their guard. An open space permits the players to run too far away which may leave some other players idle.

Indoors the space is much smaller, yet a schoolhouse offers innumerable opportunities. One can play in the classroom, corridor or gym-hall. Although it is more convenient to run in a large room, a desk-packed classroom is also held quite acceptable. Class Tag:

When a teacher happened to have left us in our classroom for the break, there was no quiz imminent, and none of the blokes was in need of copying homework from his fellows, we would play Class Tag. In the beginning everybody was moving decently between the desks, but in a few minutes desks and chairs started to be pushed in the way of the tag and soon the chase went on straight over the desks. There was always someone standing at the door to watch out for the teacher, so that, >warned in time, we could set the room in order. But sometimes it also happened that the watchman got carried away by the chase and the approaching teacher was not noticed. (RKM, KP 50, 22 (37) Tallinn Secondary School No. 37, Form 10 - Jaagup Kippar.) e

There are also cases when Tag was played across a particularly large space. The experience of the above informant includes, for example, Interfloor Tag:

In the fourth and fifth forms half the class was playing interfloor tag (2nd and 3rd floors) during breaks. /.../ On the left-hand side of the schoolhouse there were vertical pipes reaching from one floor to the other, so the nimbler boys would change floor using those pipes. (RKM, KP 50, 18 (26) Tallinn Secondary School No. 37, Form 10 - Jaagup Kippar.)

It appears that besides running Tag may sometimes involve even climbing and sliding down a pipe.

Beginning of the game. First the playground is agreed upon, as well as the rules and restrictions to the game. Most of the rules depend on the particular variant of the game. Also, it is decided whether the game will be short or long. The short form means that after someone has been touched the game will go on with the same players, whereas in the case of the long form the one touched will drop out and the rest go on until everybody but the last has been caught. The Loksa children use even different terms: the short form is called pedi, whereas the long one is termed kull.

The next crucial stage is the selecting of the tag. Various procedures may be used:

1. One of the oldest ways is counting out. The modern

schoolchildren have quite a variety of counting-out formulas to choose from

(Vissel 1993:22). As a rule these have no direct connection with the game.

Only Tag forms an exception as there are some formulas that contain the name

of the game:

| Nips, naps, null, | Snip, snap, nil, |

| Sina oled kull. | Be the tag you will. |

2. The tag may also be found by means of finger-count.

The sailor's way: This means that after "One, two, three" everybody will present 0-5 fingers. The numbers are summated and the player with that number will be pedi.(RKM, KP 5, 263/4 (2) < Loksa Secondary School No. 1, Form 8b - Vahur Valdmann.)

One can use either the longer or the shorter way to find the person. In the short version the tag is appointed with the first round. I personally believe that the method is used rather frequently, even though it is not mentioned very often in our material.

3. Another way to do it is by shouting. In Tag both the desire and the reluctance to be the tag can be expressed this way. In the latter case, everybody tries to be the first to shout: Üks, kaks kolm - mitte! `One, two, three - not me!' In the opposite case one often has to signal of his or her wish to be the first by calling out, e.g. Kolm, viisteist - essa! `Three, fifteen - the first!' Such methods have come into use only recently. Analogies can be met in Finland. Of Tag variants, the shouting method is used for Jumping Tag (Toe-Tag), being, indeed, so organically knitted to the game that it is often described as part of the very game and sometimes the game is even called after the shouting formula.

4. Some times the person suggesting the game is made to be the first tag.

5. During the game the role of the tag may be acquired by being hit fast. Thereafter the tag's role is passed over to any player who is touched by the tag.

6. Another possibility of freeing oneself from the responsibility is to touch a certain object:

The same was done for Tag. At a break when we had been talking quietly for several minutes, one of us would suddenly cry out, "Who's the last to touch the doorjamb will be the tag!" and run off in the corresponding direction. As nobody wanted to remain the last everybody ran at full speed. Many a teacher has experienced the impact of such a stampede. When the doorjamb had been reached, someone would remember another anecdote and the peaceful prattle would go on. (RKM, KP 50. 21 (36) Tallinn Secondary School No. 37, Form 10 - Jaagup Kippar.)

Central activity. Tag can be considered to be a selfperpetuating game (Opie 1984:62) whereas the basic game itself conisist of repeating a certain part.

The simplest underlying action of Tag has already been described above. In the case of the short form the game is resumed after chase is caught, with all the previous players participating, whereas in the longer form the chases are dropping out of the game in their order of being caught until the ground is clear. There is also a third, prolonged form called Releasing Tag in which free players have the power to set their caught companion free so that he or she may resume playing. But in actual practice there are numerous kinds of Tag, involving various special requirements and restrictions.

1. Methods of touching. In ordinary Tag a hand-touch suffices to catch the chase or to hit him fast. Often an Estonian tag will combine the touch with a call `Kull!' or `(name), kull!'9 In a Russian company the person touched will inform the others of his or her being caught by calling out and raising his hand (Byleyeva-Grigoryev 1985:15). Also, a person can be caught by someone stepping on his foot (for the kinds of Jumping Tag, see the chapter on Jumping Games), or hitting him by an object (ball, eraser, duster - each lending its name to the respective variant of Tag).

2. There may also be a safe zone called home where the tag must not touch the players, or if he does, it has no effect. Those places are agreed upon beforehand (e.g. window-sill, corners of a building or a room, walls, various edges, etc.). Safety may also be associated with a certain material (wood, glass, stone, iron, metal, cloth etc.) or colour (e.g. white, brown, etc.). If one holds on to such an object, or is in contact with it in some other manner, one is out of the tag's reach.

In the fifth and sixth forms we played mostly window-sill tag. One of us was the tag (pedi) who had to chase the others, those saved themselves by sitting quickly on a window-sill. But they were not allowed to remain sitting there long. The tag would count up to ten and if the chase was still sitting on the window-sill, she should be made the tag. In our class the game was very popular. It was mostly played by girls. The game helped to make the breaks exciting. The game was also sports, only the window-sill suffered. (RKM, KP 5, 44 (1) < Loksa Secondary No. 1, Form 8a - Kaarin Laane.)

If the players are allowed to move only along certain edges, we have Line Tag:

Line tag is just an ordinary tag with the exception that one could move only along the parallel straps of metal sheet nailed to the floor in order to keep the floor cover in place. The straps lay parallelly, so one could get from one row of straps to another only near the wall or where a strap had been placed perpendicularly to the others. (RKM, KP 50, 18/9 (27) Tallinn Secondary School No. 37, Form 10 - Jaagup Kippar.)

In addition to the quick and agile, often evasive movement taken for granted in any Tag variant, Line Tag requires good balance-keeping abilities to avoid stepping aside. Although relatively new in Estonia, this game is rather widely known internationally. In England it is known as line-he (Opie 1984:70).

Another example to illustrate protection offered by a certain material or colour:

The number of participants is unlimited, but the optimum is ten. Depending on whether the game is Iron, Glass or Wood Tag, one will try and get hold of the respective material so that the tag cannot hit one. If it still happens, the pupil hit will become the next tag.(RKM, KP 12, 309/10 (9) < Tallinn Secondary School No. 7, Form 10b - Raul Aarma.)

Probably some materials, like iron and wood are relicts of the ancient belief in their protective capacity. Touch Iron and Touch Wood are spread in many countries. I. Opie proved with the help of literature that Touch Iron was a popular game in the 18th century, while Touchwood predominated in the 19th century (Opie 1984:79). Estonians lack old and numerous notations of Touchwood and Touch Iron to find such direct connections. Colour Tag is a relatively new tag form in Estonia, too.

3. Safety may also be gained by taking a certain protective action (squatting, hanging, climbing). The most popular of Tag games using a protective posture is Squatting Tag (kükikull, kükakull):

When I was still younger I used to love all kinds of Tag games. The main game played during the breaks between lessons was Squatting Tag (kükiläts). One child was picked tag, whereas the rest were to walk. As the tag got nearer you were to squat down. If, however, you did not manage to do it in time so that the tag could touch you, it was your turn to become the tag. (RKM, KP 14, 566 (2) < Haapsalu Sanatory Boarding School, Form 9 - Loola Hütt.)

In the summer of 1996, a supplementary form of Squatting Tag or Mickey Mouse (Miki kull) was played - immunity from the tag could be obtained by squatting and calling out "Miki!" or the name of another hero from Walt Disney's Mickey-Mouse stories.

In northeastern Estonia children play an original game called High Tag (kõrguspütt) in which safety from the tag can be gained by climbing to a higher place. As soon as the last player has climbed up, the safe condition is off and the tag may resume his catching activity. A quite similar game was called Sandbox Tag by some pupils of Tallinn Secondary School No. 7.

4. Sometimes a special protective statement "turr!" is used. This may be attained, e.g. by counting from one to ten, then placing the third finger over the second and calling out: "Turr!" 10, or by crossing one's arms so that the hands touch the shoulders. Notably, it is the rule in any kind of Tag that the possible safety condition cannot last too long.

5. There are still other, similar ways of gaining safety. In some variants the child hit fast has to freeze "in a stony sleep", or with his arms wide outstretched until some other player sets him free again. In Releasing Tag the freeing can take place in one of the following two ways: either by touching the frozen player (e.g. Cross Tag (ristiläts), leka, Stone Figure (kivikuju), Flying Tag (lennukull, lennukas)), or by passing through from under the frozen one's straddle (e.g. Straddle Tag (harkjalakull), lennukull, lennukas). According to the rule each player can be set free not more than three times.

B. One Group Chasing Another

Running games often involve two groups of players, while one of them consists of chasers and the other one of chases. These games can be played both indoors and outdoors, but the large number of participants certainly favours a larger space beginning with school corridors and gym-halls and ending with yards, intra-section squares, streets, parks and woodland. In order to prevent players from scattering over too vast a terrain, which may turn the game tardy and uninteresting the first thing is usually to define the borders of the playing area. Like many other games, running games are not confined to their name-giving activity. Often elements of hide-and-seek, orienteering and war games are also included.

Chase (tagaajamine) is a typical running game, old and simple. Members of one team try to catch the members of another team. When all chasers are caught, the groups will exchange roles. It has not been explained how the groups are formed and whether selection is applied. Sometimes such chases may spring up between girls and boys (reports from Iisaku and Sillaotsa), or, between the pupils of two parallel forms, the children of two different town sections or villages. In this case the opposite of "us" and "them" is accented especially strongly (my own childhood experience). Those games may break out spontaneously, transition from reality to games taking place unnoticed. To simple chasing children prefer scouting (luuremäng, luurekas, lurts). As it is absent from the 1935 survey we conclude that it has became popular later than that. One is probably justified to look for traces of the terrain games played at pioneer meetings and during the night alerts practised at pioneer camps. Yet while the last mentioned games were organized by adults, the modern ones are arranged by children who have considerably "domesticated" the game adding all sorts of tricks to make it more mysterious and thrilling. The games may differ greatly as to their complexity. Traits of a running game may be combined with those of Hide-and-Seek, for example:

Scouting. This is played by boys and girls about 9-16 years old. It is best to play across a large space. In town it is not so good. Earlier I used to live in the country and there we would play almost every day. One team starts counting so that they do not see where the others are hiding. After that they go looking for the others. While one team is searching the place, the others may change hiding. If a player has been spotted, he may run away from the chaser. As soon as the chaser touches the runaway, the runaway is considered caught. When the seekers have caught all of the "enemies", the other team will start counting. (RKM, KP 43, 400 (10) Sauga School, Form 8 - Lele Aak.)

The conditions of considering the enemy caught may vary quite widely. Võru children, for example, can choose between two possibilities: either it is enough to spot the adversary (like in Hide-and-Seek) or he must be touched. If scouting is played on bikes, it is sufficient to overtake the player. Sometimes it is stipulated that the team will go scouting together, not separating at all. Often scouting represents an orienteering game in which the chased group leaves behind some token (letter, mark of direction) to keep the chasers on the right track.

My favourite game is the arrow-game in which the players are divided into two teams - chasers and chases. Besides the players some chalk is needed, as well as a large area where the game takes place. It is played as follows: first the chases will start and go either together or each in a different direction, leaving behind chalk-drawn arrows to show the direction of flight. Those arrows may be various: NB! one arrow must point to the right direction. (RKM, KP 14, 149 (9) Haapsalu Sanatory School Boarding, Form 6 - Marko Haiba, Harju County, Laagri.) When we were younger, we girls used to play such hide-and seek (or scouting game): The game was played around the schoolhouse. Every player had a piece chalk. Everyone also had her conventional sign (x, for example). I was hiding in different places around the building. From time to time I drew my sign on the wall (also in places other than where I was hiding) and the others had to find me by those signs. If I passed a place for a second time adding another cross, it became more difficult to find me. (RKM, KP 14, 565 (1) < Haapsalu Sanatory Boarding School, Form 9 - Loola Hütt, b. 1976, Haapsalu, Läänemaa County.)

C. Games with Increasing and Decreasing Groups

Games in which one team will grow at the expense of the other do not seem to be especially popular just now. Our survey yielded only two examples: Fishing Net known earlier as well, and the schematically similar Alimpapa.

Fishing Net. One player will start chasing the others and when he has caught someone they will join hands to chase the rest of the players together. And whomever they catch next will join them too. The catching will go on until the row of children is quite long and only one player has remained free. The last child to remain free is the winner. The child who was caught first will become the next chaser. (RKM, KP 26, 269 (1) Meremäe Secondary School, Form 7 - Rivo Mehilane.)

Fishing Net used to be quite popular according to the references from the 1930s. Its previous areal distribution is presented on Map 2. In the present survey, however, the game was mentioned but in a few contributions coming from western and southeastern Estonia.

Ali-Baba or Alim-pam-paa has probably been borrowed from Russians as the dialogue is almost invariably in Russian. The game-initial opposition is not between one player and all the rest, but between two rows of children standing opposite each other. Children are caught alternately from either row, while the catcher (disjoiner of the others' linked hands) is a different child every time. Children say that the game has been learnt either from Russian children or from Russian teachers.

Outdoors we play Ali-Baba. There are two sides. Both are standing at a certain distance from each other. Members of either group hold fast to each other's hands. One side must call someone from the other side out like that: "Ali-baba!" - "Achom syuda?" - "Pyatava, tisyatava (name) nam syuda!" If the child called out is able to run the others' hands loose, he is allowed to take one of the two players with him. If not, he has to stay there. The team that is drained first is the loser. (RKM, KP 42, 123 (9) Tallinn Secondary School No. 32, Form 9a - Merle Ollik.)

The dialogue may also occur in Estonian: "Alimpapa, whom do you wish?"

D. Other Possibilities

Of the rest of running games the most popular was Herring, Herring One, Two, Three reported as early as 1935 from several regions. According to our survey it was one of the most widespread games geographically. The game is also known as Silgud ritta, üks, kaks, kolm `Small Herrings to a Row, One, Two, Three' or Silguke, silguke, üks, kaks, kolm, but also Aeglasemalt sõuad, kaugemale jõuad `More Haste, Less Speed' or Sõua, sõua, kaugemale jõua `Row, Row, Far May You Go'.

In this game the relations between the players are quite different - everybody tries to be as quick and nimble as possible to catch one player (the reader). The reader reads out the formula `Sõua, sõua, kaugele jõua'. The number of players does not matter. The players move only forwards. When the reader has finished and notices someone moving, the one detected will have to stand behind the line drawn behind the reader. The reader stands near the wall. He who touches the reader can become the new reader. The idea of the game is that the child who has been the reader the greatest number of times is the winner. (RKM, KP 92/3 (10, 11) Nõo Realgymnasium, Form 3a - Vilho Meier.)

Such formerly popular games as Tagumine paar `The Last Couple' and Kolme palju `Three are Too Many' have become quite rare.

Running Games with Imaginative Elements

In the case of running games one can often meet references to imaginative elements, yet the way they are realized remains unclear as the children's descriptions are rather brief. There are two more distinct possibilities: 1) the names given to the participants are formal, not affecting the players' behaviour, (in Cat and Mouse (kass ja hiir), for example, the animals are not imitated, there is just plain chase); 2) players try assuming the character of the role.

Such role-playing is certainly improvised as usually there is no fixed dialogue. Which of the two strategies is followed in concrete cases of playing Golden Man and Thieves (Kuldinimene ja vargad), Kokovanja, Highway Robbers (Maanteeröövlid), Death (Surm), Witch (Nõid), Cossacks and Robbers (Kasakad ja röövlid) is hard to ascertain, although a certain wish to act might be presumed.

Cat and Mouse. One child is cat and the others are mice. The mice have cords for tails. The cat stands in one place and tries to catch the mice by tail. The mice are running around him.(RKM, KP 429 (1)(RKM, KP 429 (1) Loksa Secondary School No. 1, Form 7b - Raili Lepp.)

Some improvisation also benefits good old Cops and Robbers that is especially popular with younger boys. The archive files contain several names for the game opposing rascals (or thieves) and police (Varas ja politsei, Pätt ja politsei, Varas ja võmm, Sala ja suli, Sulka ja polka, etc.).

The games were very many. In old times Rascal and Police was one of the most popular. This went on like that: there had to be one or two policemen, depending on the number of the players. The rest were all rascals. The policeman or policemen had to catch the rascals and take them to prison. Several places could serve as prisons. When the police had got everybody imprisoned, new policemen were chosen. (RKM, KP 9, 198/9 (1) < Tallinn Secondary School No. 7, Form 7b - Tambet Schütz.)

Besides the old traditional games borrowed from the neighbouring nations there are games invented by children themselves, or at least looked upon as such with pride. And even if we find something similar played elsewhere as well, there is really something original either in the pattern, character names, or rules of the game. An example can be found in Vana Kõbu, a new version of the old Witch Game, invented by girls from a shool in Tallinn. The game was described by five girls. The following description is the most emotional as well as the most detailed of the five, providing the actual rules and giving an inkling of the atmosphere usually not dwelt upon.

If we wearied of that game there was another one, called Vana Kõbu handy. This game often ended in quarrel and tears as there was a lot of forcible pulling and dragging involved. The game went as follows. There were two kinds of participants: children and witches. Somewhere the witches would count up to a hundred, then move to the other end of the corridor to catch the children. Those would hold on to window-sills, hot-water pipes and other suitable places. And then the witches would start tearing their hands loose. After the game many hands were just fiery red. If a child was torn loose, she would be dragged to the witches' home and made a witch. Instead of her someone else (there was a lot of argument as to who) had to go and become a child. The game also had its rules. Tickling was forbidden. Yet in many cases this was forgotten and then the child would start crying and wailing and screaming. Next thing the witches would start shouting that they have been witches too long so they would like to be children too. Then everybody was shouting and other people who happened to be in the corridor came to beg us to quiet down. Of course nobody would hear anybody and there was overall quarrel. As a rule we did not play any other games except ordinary tag. Those two were the main games to play. Although after the big Vana Kõbu quarrel everybody promised that they would never play the game again, it would be played time and again and with great excitement. It often happened that someone lost a button from her blouse or a tuft of hair, one's sneakers were always dusty and the toes sore as it was on those that the commotion took place. Yet, thinking back, the game was horrible, but also exciting. (RKM, KP 9, 302/4 (2) Tallinn Secondary School No. 7, Form 7b - R. Kivistik.)

II. Jumping Games

During their history of development those games seem to have been the most receptive of innovations. The earlier game files of the Estonian Folklore Archives contain reports only of Hopscotch, Beds (keks), Rooster-Boxing (kukepoks) (a game in which the players hop on one foot trying to bump each other out of balance) and Rope-Skipping (hüppenöör). Elastic Skipping (kummikeks) was mediated to North Estonia by the Finnish TV only in the early 1970s, Hopa-hopa and Toe Tag (varbakull) arrived even later than that. Most of the hopping and skipping games practised in Estonia are internationally known. As Elastic Skipping is pending a special issue of Pro Folkloristica that game will not be discussed in the following survey. Hopscotch alias Beds is, by all means, the most ancient and the most widespread hopping game of today. The Estonian name keks (< keksima `to hop') is sometimes even extended to some other hopping and skipping games like Toe-Tag, Rope-Skipping etc. Enjoying a world-wide popularity, Hopscotch seems to be "played on all continents, both by civilized nations and by primitive tribes. Hopscotch being so special, it must have - in distant past - emerged at one certain place from which it has then little by little spread all over the world" (Zapletal 1984:164). As early as 1667 a British scholarly publication called Poor Robin's Almanac reported Hopscotch to have been an important game in England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Spain, Holland, Italy, Sweden, Finland and some other places in Europe for centuries (Combrie 1886:403; Vries 1957: 441). During its long course of development the game has undergone considerable changes. Being mainly a girls' game today, Hopscotch used to be a boys' pastime in the 16th-century Holland (Vries 1957:44).

In Estonia the game associates mainly with urban culture and folklore loans from other peoples, not so much with peasant culture. Supposedly the Estonians acquired the tradition from some non-Estonian urban families. Sometimes the name of the game sounds suggestive (Jewish Hopscotch (juudi keks)).

Although the first archival mention of Hopscotch in Estonia dates from 1930, the game must have been known earlier than that, as according to the 1933 reports the game was played in five different ways at least. Most of the 280 relevant reports in the file date from 1935-1940, while the figures, rules and names vary, displaying also some local differentiation.

The Estonian names of Hopscotch as well as the playing schemes reflect an intermingle of local and international traditions. The earliest origin of the game has been associated with certain ritual activities practised in ancient temples. In various countries (France, Slovakia, Holland, Russia, Ireland) there is a persistent tradition to call the finishing compartments (courts, beds) of the figure Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Those names seem to root in early Christianity in which period the players' passing through the seven courts of the figure might well have imitated the contemporary idea of the progress of the soul through the future state (Combrie 1886:406). The previous Estonian names of the game suggest a similar motivation (Heaven and Hell (taevas ja põrgu), The Way to Heaven (tee taevasse), Home and Hell (kodu ja põrgu), A Ladder to Heaven (taevakartsamäng), Ascension Game (taevaminemise mäng), Earth and Sky (maa ja taevas) etc.). The material of 1992 shows that although the words have changed, an association with the original meaning has been retained, e.g. paradiis `paradise' has been replaced by taevas `sky; heaven', põrgu `hell' has been substituted by tuli `fire' or katel `kettle, cauldron'. Maja `house' and mõis `estate' belong to the earlier name layer, denoting individual courts of rest. Some names of the game, such as ruut `square', tigu `snail', hobuseraud `horseshoe', Pambu-Peedu (reminding one of a baby in swaddling clothes), ruudumäng `game of squares', kast, kekskast `beds' (lit. `box', `hopping-box'), refer to the figure of the game or to some of its elements. On the other hand, ümber maailma mäng `round the world', or töökla (a derivative of töö `labour') emphasize the game's length and complicated nature, or its consisting of several stages (klass `class', 8-klassi mäng `eight-class game', kekskool, hüpete kool `school of hopscotch, hopping school'), or the basic activity of hopping (kekstu, keks, keksimäng, kikskast, kenkamine, kunkamine. In spite of the fact that the 1992 material includes about 60 shorter or longer reports of Horseshoe (hobuseraud), Dilly-Nilly (lill-loll, lit. `flower-fool'), Staircase Hopscotch (treppkeks), Beds (kekskast) or Ground Hopscotch (maakeks), Number Beds (numbrikeks), Stone Beds (kivikeks), Snail Beds (teokeks) and Roundy Beds (ümarkeks) (see Fig. 1), the game is not half as popular as Elastic Skipping.

What is common to all those variants of Hopscotch is the following: first, a playing area is marked off on the ground and divided into a certain number of oblong or square compartments (courts, beds); the figure is traversed hopping; the compartments are traversed in a certain prescribed order, which mostly (except with Number Beds) coincides with their normal order of succession; the game consists of rounds (classes); every class requires a different way of hopping and/or a different accompanying activity (hopping on the left foot, on the right foot, left and right alternating, feet together, legs crossed, etc.) A fault (an inaccurate hop or throw, loss of balance, etc.) means that the turn passes over to the next player.

Figure 1. Hopscotch variants: 1. Stairca

(treppkeks) or Sun (päike); 2.

Beds (kekskast), or Ground Hopscotch

(maakeks); 3. Number Beds

(numbrikeks), or Square Beds

(ruutkeks); 4. Stone Beds (kivikeks)

or Game of Squares (ruudumäng) or Beds

(kekskast); 5. Horseshoe (hobuseraud); 6a-b. Dilly-Nilly

(lill-loll); 7. Snail (tigu); 8.

Roundy Beds (ümarkeks) or Lid Beds

(kaanekeks).

Map 5.

References on Heaven and Hell (taevas ja põrgu) dating from 1930.

Hopping games can be classified according to the following differentiating features: the figure alias design of the playing ground (rectangle, square, circle, spiral or some combination of those); the course of the player on the figure (either just from beginning to end like in Horseshoe and Snail, or there and back like in Staircase and Ground Hopscotch); activities (either just hopping or hopping combined with some other activity).

The hopping game described the most often was Staircase (treppkeks). The figure represents a combination of single and double beds, producing a vague association with stairs (see Fig. 1.1). Earlier this century the game was often called taevatrepp `stairway to heaven', taevaminemismäng, taevakartsamäng, etc. From West-Estonia the name lennuk `aeroplane' has been registered.11 The figures are well known throughout the world (Finland, Holland, Ireland, but also in Africa and elsewhere). The Irish children call it French Beds (Brady 1984:158).12 Nowadays the game is called simply Hopscotch, Beds (keks), sometimes also Ordinary Hopscotch, or Sun (päike), Sky, Heaven (taevas) etc. motivated by the word written into the last bed.

The activities for Stairway are combined (accurate throw, hopping, the picking up of an object). During a class the figure is traversed as many times as there are beds, while the pickey (a piece of stone, glass etc.)13 is aimed at and picked up in a different bed every time. The behaviour in the word-bed is agreed on the spot (e.g. one may be required to hop blindfolded as many times as one's age is). For every following round the manner of either hopping or throwing is changed.

Class is a widespread term for a hopping round. According to some earlier reports from Tartu region Class (klass) or School (kool) were the terms for the game of Staircase or the Beds figure in general. Klass may also have meant just a compartment in the figure, as is the case with the name The Game of Eight Classes (8-klassi mäng). The same word (klass, klassiki) is current with the Russian (Byleyeva-Grigoryev 1985:24; RKM, KP Vene) and Polish children (Zapletal 1984:168).14

The activities practised in different classes vary locally and/or groupwise. The most frequent hopping systems are as follows: One - hopping alternately on the right foot and on both feet, according to the alternation of single and double beds in the figure; Two - one foot (mostly the right one); Three - one foot (mostly the left one); Four - feet together; Five - legs crossed, etc. One may also be required to hop backwards, blindfolded etc.

With time the game seems to have become more complicated. Earlier, one of the goals may have been the collection of individual beds of rest, called House (maja) or Home (kodu). For every round faultlessly completed the player was entitled to a `House'. Whoever was first to collect three such `Houses' was declared winner. Modern rules do not care for rest beds.

Not too different from the Staircase is Hopping Beds (kekskast) (Fig. 1.2) of which the school tradition knows several figures. It is also quite widely known internationally, being played, for example, in Slovakia, Russia, North Africa, England, Santo-Domingo, Holland, Hawaii (Zapletal 1984:166-167), Ireland (Brady 1984:157), France (Lukachi 1977:68).

It is even possible to regard Staircase as a variant of Hopping Beds in which the `envelope' bed has been analysed into a single-double-single scheme. According to the rules of Hopping Beds, a player was never to land in Hell, so Heaven had to be reached with one hop. Sometimes the beds were given conventional religious names that tied them up in a legend (e.g. A Visit to Heaven (taevaskäik): beds 1-2 Entrance to the World (eesmaailmaruum), the quadruple bed 3-6 Crossroads of the World (maailma risttee), the double bed 7-8 Hallway to Hell (põrgu eeskoda), Hell (põrgu), Heaven (taevas); or 1-2 Thief (varas), Quadruple Bed (nelikkast) or Envelope (ümbrik), the following double bed Witch's Hatch (nõialuugid), then Hell and Paradise). Nowadays the game is not much known any more.

According to archive materials Number Beds (numbrikeks) (Fig 1.3) is one of the newer kinds of hopping games, not recorded during the 1934 collection campaign. It probably arrived in Estonia in mid- or late 1960s, and in 1972-73 Number Beds was a well-known game (RKM II 306). The figure represents a square or a rectangle that is divided into 9, 12 or 24 compartments. Often an additional square (`foot') is joined to the middle square of the front or back row. The numbering system varies, but usually the neighbouring beds are not marked by successive numbers. Here hopping is the only activity: the player is to traverse the figure precisely in the order of the numbers.15 Only the manner of hopping varies: 1) feet together, 2) on the right foot, 3) on the left foot, 4) backwards. Depending on how inventive the players happen to be the game may be prolonged and diversified further (e.g. the figure may have to be traversed in the opposite order, or blindfolded etc.). Every class consists of as many rounds as there are squares. For "one" all beds have to be taken, for "two" all except the first, etc. Rest beds or "rest homes" may also be involved, sometimes even lending their name puhkekodud to the whole game.

Stone Beds (kivikeks) (Fig. 1.4) is another old game that is well known internationally. The name originates in the throwing of an object or pickey. The figure chalked on the ground represents a rectangle consisting of `beds'. To begin with, a piece of stone is thrown into a certain bed, next the beds start to be traversed hopping on one foot. When the stone is reached, the rest of the hopping is combined with kicking the stone from bed to bed. At that the stone should keep clear of the lines. The hopping starts from the lower right hand corner and ends in the lower left hand corner, or vice versa. In some variants the stone is kicked only once - just into the next bed. A similar practice is sometimes involved with Number Beds. In some cases the one kick was meant to get the stone out of the figure.

Frequently there occur cases in which certain basic actions are combined for different kinds of figures. A stone pickey may, for example, also be thrown into the figures of Staircase or Hopping Beds, to be returned by the player hopping on one foot. The beds are usually numbered counterclockwise, but the opposite direction is also possible. In rare cases the enumeration follows a zigzag course (Fig 2). There may also be a word-bed at the farther end of the figure. And there is an exceptional report from 1940, according to which Heaven and Hell had been placed before the starting and finishing beds.

Dilly-Nilly (lillike-lollike or lill-loll) is a new hopping game played in a group. The number of beds being but 3-4, there are not so many variants. The figure may consist either of three successive beds or of a square divided into four smaller ones (Fig. 1.6a-b). This is a blind game, i.e. the hopping is done with one's eyes closed. The companions keep a close watch on the player and react on every hop of hers. An accurate hop (clear of the lines) is welcomed with an approving shout Lill! `flower!', whereas a fault is received with Loll! `fool!'.

Lill! qualifies the player for the next hop, Loll! means that the turn has to be passed on to the next player. Class 1 is hopped feet together, Class 2 on the right foot, etc.

The figure used for Snail Beds (teokeks) is a spiral consisting of up to 30 beds. Sometimes a snail's head is added (Fig 1.7). The hopping is done either on one foot or feet together from the head of the snail to the centre, and if previously so agreed, all the way back as well. The "out" rules are as usual. A spiral faultlessly traversed entitles the player to an individual rest bed called maja `house', kodu `home' or puhkekodu `rest home'. The marked rest bed is reserved exclusively for the owner, nobody else may even land there. As every new class produces at least one new rest bed they are tried to be selected so as to make the owner's life as comfortable as possible - at the expense of the others. If two rest beds lie side by side, the other players have to make a longer hop into the next free bed. Home and House being old names for rest beds, the new one of Rest Home may lend its name of puhkekodu to the whole game. Descriptions of Snail Beds are predominantly from North Estonia, which was the case also in 1930. An additional questioning revealed that to a certain extent the game is also known in some other parts of Estonia. This game also enjoys an international repute.16

In Horseshoe (hobuseraud) (Fig 1.5), the hopping is done on one foot. The player is declared "out" as soon as she loses balance, i.e. "as soon as her hand touches the ground". The game may be played with a piece of stone, every faultless round entitles the player to a rest bed. Or children may get ready for the game by marking off two rest beds (Parking Lots) that are free for every player to use. Wins the player who finds herself still hopping when everybody else is "out".

According to the 1930 material the game was known above all in central and southern Estonia.17

A. Vissel (1996).

The figure for Roundy Beds (ümarkeks) consists of two circles, one within the other. The area between the circles is divided into 8-10 sectors which are numbered counterclockwise. The last number (usually 9 or 11) is written into the small circle (Fig. 1.8). The actions fall into two classes: in the first class the numbers are passed through either 1) hopping on one foot, finishing the series by landing both feet in the small circle, or 2) on two feet while either foot (L=left, R=right) must land in successive beds. Here hop 1L2R is followed by a backward hop (8L1R), and only then a hop forward 2L3R may follow. So the course of the player on the figure can be formulated as follows (backwards hops are in parentheses): 1L2R+(8L1R); 2L3R+(1L2R) etc. Unlike the other styles of Hopscotch, in which the main problem lies in hopping on one foot or backwards, Roundy Beds means problems in two-feet hopping. In Class 2 the player has to hop into beds dictated by the others. The maximum number of beds so dictated is three.

After completing this series of three hops the player will land both feet either in the small circle or outside the figure. The numbers are called out either at random or selected according to a system (e.g., all numbers in the first series have to include 1, the second series requires 2, etc.). Sometimes the game is combined with mnemonic elements. In this case in addition to numbers the beds receive names like Boy's Name, Girl's Name, Bird, Tree, Vegetable, Fruit, Article of Clothing, Footwear, Magazine, Newspaper. Only the small circle remains free of a name.

Besides hopping, the player has to quickly call out a word or name as required, thus exerting both her physique and intellect. The word classes remind one of the popular questionnaire-game called Bird, Animal. A few variants of Roundy Beds were noted down in the 1930s, Days of the Week (nädalapäevakeks) (see Fig. 3.4). In international tradition the round figure may occur either separately or as a component of a larger figure.

Skipping Games

Skipping games are played both alone and in a group, and they are rather popular. Rope-Skipping has been a favourite pastime with generations of girls, while boys have not been especially interested (although at primary school lessons of physical training both boys and girls are introduced to it alike). Probably the skipping-rope was first introduced by schools, but there is also evidence of it having spread from other sources. Notably, although at lessons of physical training teachers used to teach different styles of rope-skipping and use it as an exercise, no games or "Skipping-School" were taught. Rope-Skipping was rather popular in the 1950-60s. Numerous mentions and descriptions were also received in 1992, the number of reports amounting to a third of those dealing with Elastic Skipping and to a half of those concerning ordinary Hopscotch.

Skipping-School is familiar to many peoples (Zapletal 1984:190; Byleyeva-Grigoryev 1985:25 et al.) It consists of classes requiring a definite number of certain exercises to be performed: Class 1 - feet together; Class 2 - skipping alternately on either foot, while the right foot comes down first; Class 3 - skipping alternately on either foot, while the left foot comes down first; Class 4 - on the right foot; Class 5 - on the left foot; Class 6 - legs crossed; Class 7 - feet together, while the rope is crossed. Throughout all these classes the rope moves from the front backwards. The following classes are similar except that the rope moves in the opposite direction. The number of skips (10, 12 etc.) is previously agreed upon. Sometimes a verse is used to accompany the skipping and to determine the number of skips at that. In many places of Estonia either one or the other of the two verses to follow was used:

| Vanamees, vanamees, | An old man, an old man, |

| kuuskümmend kuus, | sixty-six (years old), |

| poolteist hammast oli suus. | his teeth were one and a half. |

| Kartis hiirt ja kartis rotti, | Feared a mouse and feared a rat, |

| kartis nurgas jahukotti. | feared a flour bag in the corner. |

| Paks Margareta | Fat Margaret |

| tahtis suppi keeta. | wanted to make soup. |

| Tal ei olnud moosi, | As she had no jam |

| hüppas tuhatoosi. | she jumped into an ash-tray. |

It often happens that upon the reciting of the verse the rope is hurled to the ground so that a ring is formed in which the player must either count numbers up to her age, or hop as many times before she may proceed to the next class. In some references every skipping exercise used to be repeated as long as the player could faultlessly do it. Winner was the girl with the highest score. Usually Skipping-School ends with an exam in which every class is repeated just once.

Skipping in a Group (Long Rope Skipping)

This style of skipping is practised in several countries (Finland, Ireland, etc.). In earlier times it often meant that a longer rope was used. Although some simple games of rope-spinning have been described among older Estonian folk games, rope-skipping games, that are slightly different in form, seem to have been borrowed from abroad. The skipping is done to short verses of 3-4 words or a couple of lines. Such skipping to verses is practised both by our close neighbours (see, for example, Virtanen 1970:153) and by some more distant peoples (Brady 1984:69).

Skipping to a rhythmical chant is probably also a relatively recent phenomenon in the Estonian children's lore. The name of Roose, Marie, Mak, also called Ox (härg), Roose, Marie, Mak; Rose, Carnation, Tulip (roos, nelk, tulp); Skipping-Rope Skipping (hüppenööri hüppamine) is mostly motivated by the verse recited to the game. Usually it consists of a series of girls' and/or flower names, some of which may be in Russian or adaptations. Roose, Marie, Mak occurs in parallel with a Russian rhyme Roza, beryoza/ mak, durak `rose, birch/ poppy, fool', or Roza, beryoza/ liliya `rose, birch/ lily', mak or roos, nelk, tulp `Rose, Carnation, Tulip'. A shorter or longer list of Knife, Fork, Spoon may also be used. The function of the reciting is to help keep the rhythm of the game. Usually there are three players, each of whom picks herself a name from the list. The player at whose "name" the skipping stops short, becomes the next one to skip.

The Bells will Toll (kellad löövad) is a peculiar game of rope-spinning, in which the rope spinners precede the spinning with the words "The bells will toll ... times". This informs the player of the number of times she will have to skip clean of the rope.

Fisherman (kalamees) was sometimes played at lessons of physical training in the 1960s. It was described in a book titled Mänge ja meelelahutusi `Games and pastimes' (Byleyeva-Taborko-Shitik 1954:20/1) as Rod and Line. The first archival records date from the late 1980s. In this game one player (the "fisherman") is standing in the centre and eddying a rope quite near the floor, the others have to skip over it until someone gets caught in the rope - to become the next "fisherman". No exceptions to this routine are known. New games are often welcomed with great enthusiasm. The case of Fisherman has been described as follows:

It was played during breaks between lessons. Soon the whole corridor was full of 1st to 9th-formers. Of older students mostly boys took part. The schoolmaster and teachers watched us with astonishment. If anybody had to find somebody, the crowd made it quite hopeless. Our schoolmaster is 2 metres tall and even he skipped along, just in order to be able to reach the other end of the corridor. But now the game has been in oblivion for a few weeks. The older students play Ping-Pong, while the younger ones just run about. (RKM, KP 43, 526/21 < Sauga School, Form 9 - K. Päll.)

Other Jumping Games

Hopa-hopa is a game played mainly by primary school girls at breaks between lessons. In this game one has to manage to bring his or her feet together from an astride position by an alternate movement of heels and toes. It was first described in 1989.

The players are hopping "scissors", fashion to the following verse:

"Hopa-hopa-hopa, Ameerika, Europa, Jaapan, Kitai - ... nimeks sai!" (Kitai `China' in Russian; nimeks sai `got the name'.) Wit the last words one has to jump astride. Now the leader (whose name was called in the verse) will tell a number, 3 for example. Next the player has to bring her feet together by turning just on her heels and toes. If the player fails to bring her feet together with the exact number of turns called out, she has to turn round with a hop with her back to the leader and start anew. Sometimes one may jump so that the feet remain very little apart, so that bringing them together takes but a few moves. But then it may happen that the number called out is too large for the distance to be covered, and the player has to hop backwards again. That game is usually played by two, but it can also be played in a circle. In this case the leader stands in the centre. The game is a good pastime for warming up one's feet while queuing up for a bus. (EKRK III 34, 7 < Tihemetsa - Annika Matson (1989).)

Photo 6. During breaks, varvas is played. Nõo Basic

School, Form 3a. Photo: A. Vissel (1995).

With reseravations, Hopa-hopa could also be classified among some recent singing games as the first half involves the chanting of a verse to which the hopping is done in "scissors" fashion and which is quite a unique way to declare the next leader. As to the verse, most variation is observed in the third line in which Japan may alternate with Australia and Kitai with Italy - Itaalia (Itaali). Sometimes failures are punished by as many fillips as many moves the player happens to have missed. In most cases, however, the sinner must either stand facing the outside when the next round starts, or quit the game. Probably the sources of the game are Russian, in Finland it is not known.

Toe-Tag (varbakull), also Toe (varvas), Toe-y (varbakas), Two-Fifteen (kaks-viisteist), Toe-Tag (jalapedi), Hopping Game (hüppemäng), Onto the Foot Hopping (jala peale hüppamine) is a relatively new game played in Tallinn schools since the mid-1970s. The players are standing in a circle. The aim is to hit one's left-hand neighbour's foot in one hop. There is no one tag. The first tag is the boy who after the chorus Kolm, viisteist! `three, fifteen!' is the first to shout Essa! `first'. Then he has to hop hitting a foot of his left-hand neighbour. The neighbour, in turn, is allowed to hop aside to dodge the tag. The hit one will be "out". If he was not touched, he has the right to attack his left-hand neighbour. In some variants the failed hop of the tag can be returned by the attacked one. If that hop is a success, the tag is "out". Sometimes a skillful tag is allowed an extra hop. Wins the last in the ring. With Toe-Tag the beginning may also vary:

Varvas: a hopping game (for boys). The players are standing with one foot stretched forward so that the players' toes meet. One will say "Go!" and all will jump backwards as far as they can, and stay there. Next the player to start the game is picked and the direction of playing (clockwise or counterclockwise) is settled... (RKM, KP 8, 10/1 (4) < Tallinn Secondary School No. 7, Form 4c - Kristjan Jaak Kangur.)

Conclusion

Children's games today are a complex that has evolved during a long history and in which the old has mingled with the new. A thorough analysis of different layers would require a deeper knowledge of the background of the games of Estonians and their neighbours as well as the wider cultural area. Thanks to the Estonian Folklore Archives' collections of games in the 1930s and its school traditions collection of 1992, there is a good overview of the games played at that time.

Children's game is a genre of folklore that contrary to, for example, folk singing and folk dancing, to a larger extent spreads traditionally: among the peers or passed down from the older generation to the younger. It adapts itself with the everchanging, excessively urbanizing and technocratic society.

Several connections of the traditional and the innovation appeared on the level of the game's type, sort and version in kinetic (running and jumping) games. Kinetic games originate from the peasant culture. They have maintained their popularity and have quite well adapted to the present lifestyle, mentality and aesthetics. Tag game continuously attracts new generations of players. According to Estonian data this simple game has gone through some major changes during the past 60 years, although the main action and the name have remained the same.

Despite the generalizing effect of written language, there are still amazingly many old local dialect names for games in use. They mark the (personified) catcher (kull) or a light touch (lets, etc.). The current predominant name kull is a unique mixture from both Scandinavian and Slavic influences.

Today in many of the subgenera, role changes are tried to be delayed by using a more complex game structure (short, long or stretched game version) or to the so-called defence system. A short-term protection can be provided by a safety zone (kodu), contact with a certain material or colour, a certain defence position or (magical) defence condition. The number of objects providing protection has grown, but the most commonplace are still wood and iron.

Traditional counting out verses are used that (except for a couple of special tag counting outs) are not connected to any definite game. Reading the counting out rhyme has developed into a ceremony. To the long counting out rhyme, a number or word is added. The maximally long-stretched counting out is opposed to newer methods like throwing fingers, a (negative or positive) responsive call, choosing a player that has in some way come to the attention of the rest (the last to join the group, the one who made a proposal). Sometimes other games are used to start a particular game.

Tag's playing possibilities and playing activity have widened remarkably. It is a running game, in many of its subgenera the participants jump, climbe, cycle or skateboard. Thus there appear connecting lines between jumping and throwing games. Throwing and riding tags are among the games that need additional gadgets.

Three more frequently occurring situations can be found in running games: one player chasing another or the rest (A); one group of players is chasing another such (B); games with growing and declining groups. The exception is Herring where everybody is striving to reach one. Running games that are participated by two groups of players (B) have a structure close to that of tag, but the forces of those chasing and those being chased are balanced. In the games of group B the game's fate is determined by the co-ordinated actions, skill, smartness of the both groups. Group A is characterized by an endless repetition of actions, whereas group B has a clearly defined beginning and end, which comes when one of the groups has managed to accomplish their task and have won. Tag, like other so-called chain games (including games increasing and decreasing groups) does not know the meaning of the word "victory". War games is an old kind of games. Children's games today are strongly influenced by the scouting and orienteering games that have become commonplace through youth organizations.